A Road Less Traveled Toward the Greater Good

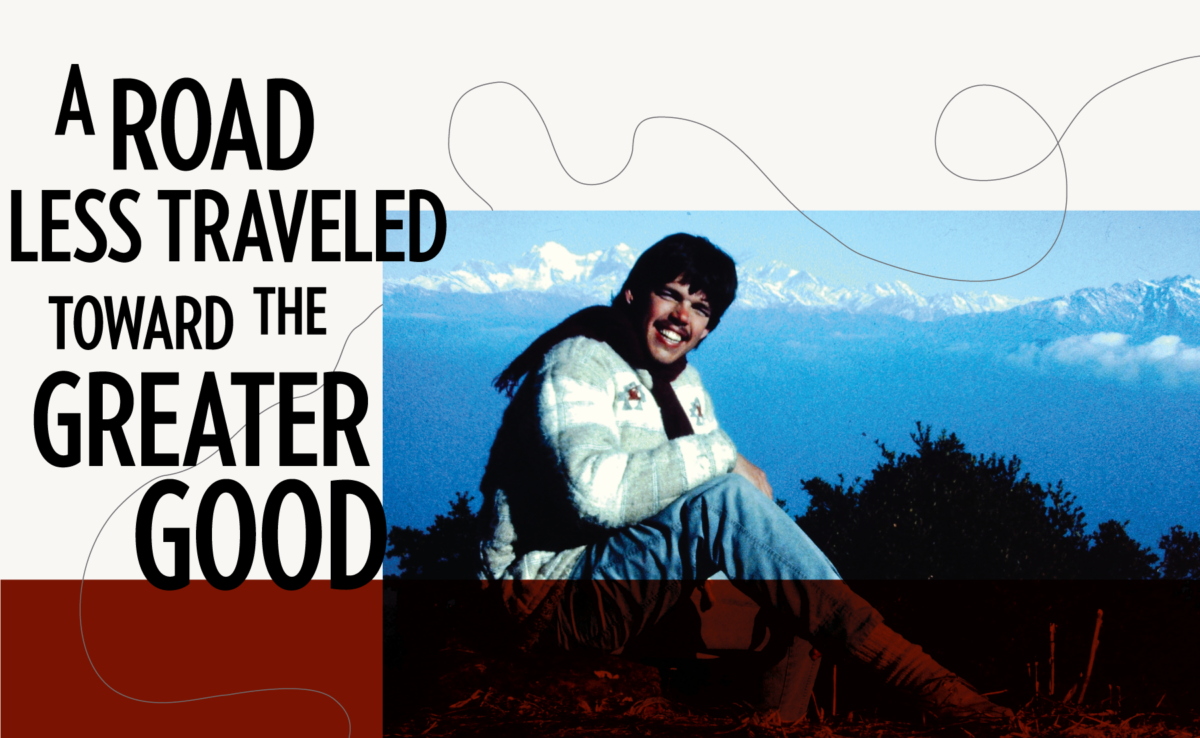

After a six-hour bus ride to the west of Kathmandu and three days walk more from the bus stop into the Nepalese village where he would conduct an ethnographic study for his thesis in anthropology, Daniel Vermeer ’88 had traveled one uncommon road in what had already been and what would continue be a career full of uncommon roads.

The off-the-beaten-path journey into Barpak did not faze Vermeer; he had lived and traveled in remote areas of Nepal and India before. Immediately after graduating from Hope, his quest to not go to graduate school, to not get a job, but to live in South Asia had been realized. In the late 1980s, Vermeer — fascinated with Buddhism, Hindi and Asian culture, determined to experience life outside a status quo existence in the United States — worked and lived as a volunteer at a crisis center for travelers in Nepal, scored a private audience with the Dalai Lama, and joined a study program and lived on Gandhi’s home ashram.

By 1990, though, Vermeer had reneged on that post-Hope-graduation declaration to never enroll in graduate school. So, there he was in Barpak about to embark on extensive fieldwork and research for an advanced degree from the University of Virginia. Yet, where Vermeer would end up today — as the founding and executive director for Duke University’s Center for Energy, Development, and the Global Environment (EDGE) at the Fuqua School of Business and associate professor of the practice — is what his massively inquisitive mind and a liberal arts education were made for.

Now, before you proceed with the rest of this story, know this: Vermeer never took a single business class at Hope, and the extent of his natural science coursework came by way of Hope’s general education requirements. Yet, according to his Duke bio, Vermeer’s expertise includes sustainability strategy, risk management, energy and behavior, value chains, resource productivity, water and ecosystem services, sustainable agriculture, industrial efficiency product certification and sustainable development. Then this: His current research focuses on natural capital considerations in business decision-making, water risk and resilience, cleantech urban development and energy innovation in emerging markets.

How does a Hope psychology and philosophy double major, with a religion minor, on-track to become an anthropologist, end up as an expert on the cutting edge of the world’s biggest business and environmental ethics questions? The answer was found at the end of the long road that led him into that remote village in Nepal.

“I was so struck by how much impact the global economy had in the far periphery of the world,” says Vermeer. “When I went to Nepal, my intuition was to try to get outside the bubble. I didn’t even know what the bubble was. But somehow, I had a sense that there’s a boundary, and I wanted to be outside of that boundary and to try to understand what that was like. Then I got to Nepal, walked three days to Barpak from the nearest road and the place is shot through with the forces of globalization, deforestation, political upheaval. The whole agricultural economy was structured by forces that were far from those local communities. The national government was trying to impose an outside educational system. So, what I realized is that I was trying to get outside, but there’s no outside. We’re all in this big global bubble together.”

Vermeer finished his master’s degree and was all-but-dissertation away from a Ph.D. in anthropology. But with the epiphany he had in Nepal, Vermeer downshifted to a hard stop like a trucker coming in hot to an off ramp. He started to see that, early in their careers, many anthropologists studied people groups that eventually are no longer on earth, “wiped out by civil war or deforestation or natural disasters,” he said. “I realized I didn’t want spend my life as a eulogist, writing the postscript to groups that no longer were around. I wanted to help find solutions for those groups, and others, so they, we, do not just survive but flourish.”

To begin to gain knowledge and experience toward that new goal, Vermeer entered a new Ph.D. program in learning sciences at Northwestern University, where he conducted research for a year on organizational learning and product development at Xerox PARC in Silicon Valley at the beginning of the booming dot.com era. After graduation in 1997, he became a consultant to Bank of America, GE, Walmart, Dupont, The Nature Conservancy and UN Global Compact, and other public and private organizations working on massive projects to affect organization change at behemoths of business.

When The Coca-Cola Company came knocking on his résumé in 2001, Vermeer says he just about didn’t open the door, not even a smidge. “What would I do at a sugar water company? That was the farthest from my mind,” he said.

Since he had fallen in love with working on weighty organizational challenges that require points of intersection with business strategy, though, the more he thought about it, the more he realized it was a chance of a lifetime to consult to upper-level executives in the most global company in the world. “It was what I dreamed about 10 years earlier while sitting in an anthropology program with zero credentials,” he says.

For seven years at Coke, whose international reach extends to the most far-flung corners in the world with two billon servings sold a day, Vermeer instituted and led the company’s first Global Water Initiative. While he looked for ways to protect the quality and availability of the company’s primary ingredient, he found methods to do the same for people in the communities from which the resource came. He did it by designing new risk management methodology for Coca-Cola’s global manufacturing facilities, which resulted in the company’s Community Water Partnerships program of nearly 500 public-private partnerships in over 90 countries.

To many people, “business ethics” sound as oxymoronic as saying something is “awfully good.” To Vermeer, that first oxymoron screams of opportunity to get to the achievement of the second. To substantively address any of the issues that need attention, he revels in engaging the players who have the majority of the impact to answer this question: Can you get big bureaucratic companies to care about big global issues for the greater good?

“Finding out what the alignment is between business interests and the world’s interests is the goal,” he says, “and I don’t think it’s altruism. It’s never been. That’s not an effective lever for change. It’s to demonstrate the alignment of their business actions in a way that benefits them, but also benefits the world. That’s basically the case that we need to make… over and over.”

Which is what he did at Coke until 2008. When he left Coke to teach and create EDGE at Duke that same year, Vermeer found a place where he could help develop additional leaders to address the most critical social and ecological problems of our day in an interdisciplinary way. With EDGE’s three-pronged approach of education, thought leadership and collaboration, he and a decade’s worth of students and other leaders have reimagined the oceans’ blue economy. Beautiful and mysterious salt waters are responsible for producing at least half of the world’s oxygen and 80% of its biodiversity. Yet, it is also estimated those waters generate three trillion dollars a year from fishing, biotechnology, tourism, and shipping. In fact, a whopping 90% of the world’s products are transported on waterways.

It’s no secret, though, that the oceans are in declining health due to over-exploitation, climate change, plastic waste and other factors. “The oceans’ fate is our fate,” Vermeer warns. And with that exhortation, Vermeer’s Christian worldview to be faithful and fastidious stewards of earthly (and oceanographic) resources echoes writer and environmental activist Wendell Berry’s prose that “to cherish what remains of the Earth and to foster its renewal is our only legitimate hope of survival.”

With each stage of his career, Vermeer has asked pressing questions, gathered data, and formed conclusions that matter most to him. He credits a pantheon of Hope professors —Boyd Wilson (religion), Charles Green (psychology), Jack Ridl (English), Nick Perovich (philosophy) and the late Art Jentz ’56 (philosophy) — with encouraging him to think broadly, intensely, creatively. None could have predicted he would journey from Nepal to Coke to Duke, but Green says he’s not surprised that’s where Vermeer went and what he’s done. “Dan thinks deeply about what he wants to do and who he wants to be and then creates that path for himself,” Green says.

“I have no doubt that Dan ended up where he is today because of his great curiosity and inquisitive nature,” Wilson adds, “but also, and this can’t be forgotten, because of his hardworking and diligent nature.”

Back at Hope this past February to deliver the annual John Shaughnessy Psychology Lecture, titled “Ocean Futures: Making the Blue Economy Green,” Vermeer told the mostly-student audience that while his career may have been meandering, it also has been purposeful. “Careers can’t always be ranked in a linear metric of success,” he assured.

Which means Vermeer’s curvy career path helped him define and find what he was good at and the world needs. Like his circuitous route to Duke, the knotty problems Vermeer works arduously to solve take some time to unravel. But eventually he gets there.