Post-WWI Campaign Brought America’s Diversity into Focus

Jeanne Petit, Ph.D. | Professor of History

The year was 1918. The United States was in the midst of World War I.

Like today, the country was going through a great deal of change, particularly in how people expressed their faith. The war triggered a wave of immigration to the U.S., bringing Catholics — and to a lesser extent, Jews — to a nation in which Protestants were the dominant religious group.

“There was a lot of tension between Protestants, Catholics and Jews,” says Dr. Jeanne Petit, who in 2017 wrote an article on one of the first interfaith fundraising campaigns in U.S. history — the United War Work Campaign.

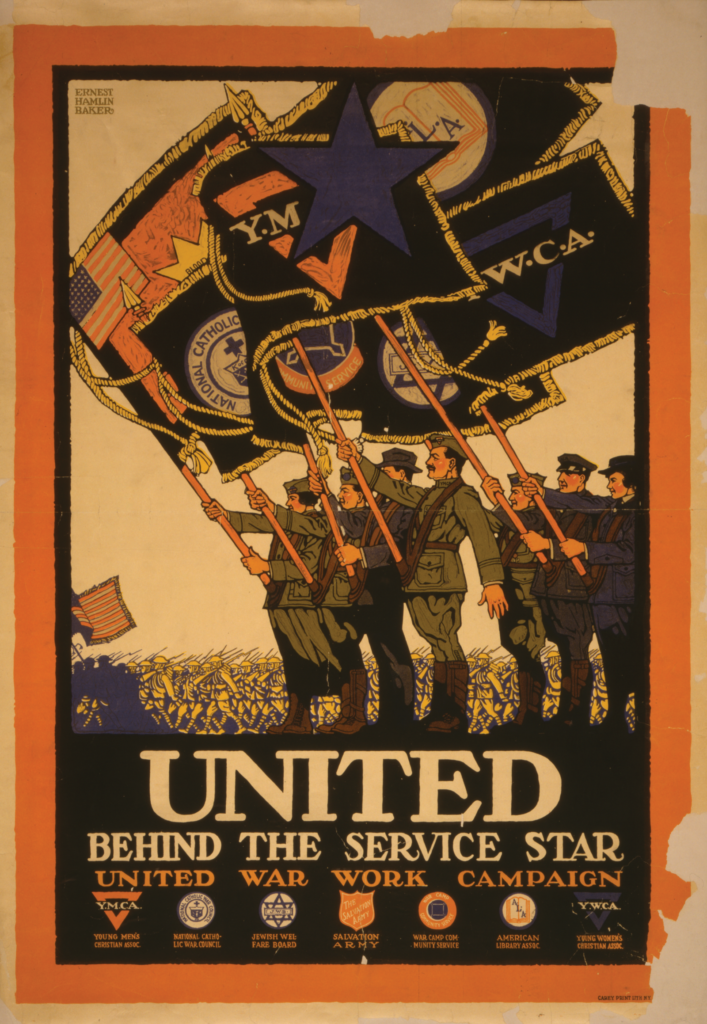

Seven non-governmental organizations, most faith-based, took part in this campaign coordinated by the U.S. War Department. They included the Catholic fraternal organization the Knights of Columbus, the Jewish Welfare Board and three Protestant groups: the YMCA, YWCA and Salvation Army. Over several years, Petit and her student research assistants pulled information from a variety of sources to explore the conflicts between the various organizations.

“You see the YMCA getting annoyed with the Knights of Columbus and vice versa — the Knights of Columbus thinks the YMCA is trying to convert all the Catholic soldiers,” Petit says. “You get multiple points of view of what’s happening.”

The United War Work Campaign’s goal was to raise $170 million to provide entertainment for U.S. troops. Plan A was for each group to pursue its own fundraising effort, Petit explains, but the Secretary of War, concerned about potential backlash from so many separate campaigns, insisted that they work together.

The campaign launch date was Nov. 11, 1918. Ironically, on that day the armistice was signed in Paris to end the war. However, the United War Work Campaign proceeded as scheduled, since U.S. troops wouldn’t return home until the following year. It exceeded its goal, raising more than $200 million.

Petit notes that valuable lessons came out of the campaign. “Protestants couldn’t just rule the roost anymore,” she says. “Other religious groups had to be taken into consideration.” Nearly 25 years later, some of the same organizations teamed up to support troops during World War II, leading to the creation of the United Service Organizations, or USO, which continues to entertain soldiers.

Several grants have supported Petit’s research, including a Great Lakes Colleges Association grant that enabled four of her Hope College students to conduct research on the United War Work campaign at the Library of Congress in summer 2015. They used the information to create a website.

In 2016, she engaged with another group of student researchers who built a website about the city of Holland’s involvement in World War I. Petit doesn’t expect that such websites will replace books and papers, but she sees great value in them. “It brings it alive in new ways, rather than just being published for historians to read,” she says.