Food for Thought

You recently finished one holiday meal and will soon belly up to another. As you sit down to partake of whatever traditional Christmas menu is yours, put your fork on pause and consider this: How many things does your food affect?

Health. Check. Culture. Check. Economies. Check. Arts and science. Check. Dispositions. Check. Your waistline. Sigh…Check.

How about history? That gets a double check from Dr. Lauren Hinkle ’04 Janes, and she’s the perfect Hope professor to explain why.

Janes is a food history scholar and the author of one book on the subject with another forthcoming in 2020. She uses food as a lens through which to teach and write about history’s many themes because the ways foods have moved, been assimilated and then incorporated into global cuisines are as much about human history as any war — the unfortunate and common view of worldwide record. And frankly, food is more fun to talk about.

If we are what we eat, then Janes’ scholarship proves that the transformative power of food makes us more multinational than we think. Those potatoes there? They were first cultivated in the Andean highlands of Peru and Bolivia as early as 3400 B.C., entered Spanish cuisine as peasant food in the 16th century, and became beloved internationally sometime in the 19th century. That sugar in your just-about-everything? Its cane was first raised in Asia, then made its way to the Mediterranean realm via Middle Eastern exposure in the 13th century, and ultimately contributed to one of the greatest travesties of human history – the trans-Atlantic slave trade. And what of corn, or maize? It originated in the Americas and is now grown worldwide, even though American corn has played a central role in international food aid since the 20th century.

Those examples are all the subject of Janes’ next book, Nourishing the World: A Global History in Three Foods and One Dish, currently under contract for Hackett Press and in the writing stages for Janes. (Her first book, Colonial Food in Interwar France: The Taste of Empire, was published in 2016 by Bloomsbury Academic.) While those three staples — potatoes, sugar and maize — explain much about trade routes, colonial development and cultural practices, it is the dish of curry that allows Janes to dig into modern imperialism, and the focal point there is India.

“The term itself, curry, comes from the British,” Janes says. “No one in India called any of these vast variety of different dishes by one name. Before the British, ‘curries’ all had their own names and regional varieties and were not at all considered the same thing. But the British saw all these different dishes of meat with a spice sauce and called them curry. A couple different varieties of it were consolidated and homogenized as the British understanding of curry, and that’s what gets imported into Europe.”

All of this matters to Janes as a historian for a couple reasons. First, she believes strongly in the embodied, physical experience of history, and studying food is a natural way to live into that reality. Second, complex food, meaningful food, necessary food is a unique means with which to explore world history more cohesively. Each rationale points to a professor prioritizing the tasteful bounty of the liberal arts.

“We can fall into this trope of the history of Western values moving elsewhere,” explains Janes, an associate professor who returned to her alma mater to teach in 2013. “So, it’s just the history of Europe expanding. And of course, we know that’s not the whole story, and potatoes are an interesting way to see that in another direction.”

All of this matters to Janes as a person, too, because, in fact, food is personal. Though she wouldn’t necessarily call herself a “foodie” (yet she does grow her own ingredients for homemade pickle relish and salsa verde in her modest garden), Janes knows how the richness of what we eat helps us tap into our own vibrant histories, hers included. Her vivid recollections of walking a Parisian street, warm baguette in hand on her first trip there as a middle schooler, portended what she would eventually study at Hope — French, history and religion — and in her doctoral dissertation at UCLA — French history with a good portion dedicated to food history. These days, the Holland Farmers Market is her happy place, a spot to fill her own basket with earthly delights as well as Hope students’ minds with educational opportunities. She takes her First Year Seminar class there in the fall to discover the culture of celebrating fresh food in community.

Cooking Potatoes

the French Revolutionary Way

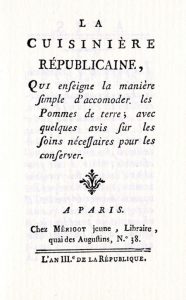

A French Revolution cookbook was published to encourage women to be thrifty with their food consumption by using less bread and more potatoes in their cooking.

The text in translation: “The Republican Cook, which teaches the simple way to use potatoes; with some advice on necessary steps for preserving them.”

From Madame Mérigot, La Cuisinière Républicaine, 1794

Radcliffe Institute of Advanced Study at Harvard University

And then she goes and does the same in a more food-centric place each spring. Janes and colleague, Dr. Heidi Kraus, associate professor of art and art history, teach an annual May Term in Paris called “Art, History and Global Citizenship in Paris,” and as you’d expect, food finds prominence in lesson and social plans in markets, restaurants and picnics.

Away from the classroom and France, Janes has led Hope history students on research jaunts to the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive at the University of Michigan as well. Funded by a Pagenkopf Research grant in the summer of 2016, she says four student-researchers — Noah Switalski ’18, Leland Cook ’17, Margaret Dickinson ’17 and Natalie Fulk ’18 — were instrumental in building an annotated bibliography for each chapter in her new book.

“They were so helpful to me in finding primary sources,” Janes recalls, “but they each wrote their own papers on food history, too. They then presented at the history colloquium as well at Hope’s Celebration of Undergraduate Research. It was great to see them really take on this subject.”

Of all the foods affecting world and personal histories in tandem, sugar could very well take the cake. The now-ubiquitous sweet stuff is celebrated as much today as it was six centuries ago. First cultivated in southeast Asia, then eventually dominating agriculture in the West Indies, sugar was initially considered precious from a European perspective because of its paucity and expense. “So, it’s associated with luxury and special occasions,” explains Janes. “That’s where we get the tradition of fancy celebratory things focused on sugar and sweets.”

Janes adds that Caribbean anthropologist and food history pioneer Sidney Mintz makes an interesting argument that sugar fueled the Industrial Revolution even as it was the main culprit for the trans-Atlantic slave trade. “He says, as sugar got planted, grown and harvested by slave labor in the West Indies and then shipped back to Europe, now they had these cheap calories for workers. In England, things like heavily sweetened tea and porridge sweetened with treacle, or molasses, increased the caloric consumption inexpensively.” That then allowed workers’ higher caloric expenditures which in turn affected increased industrial production.

Today, common, cheap sugar still maintains its fête status even though it’s everywhere, in everything, for everyone. “And though a lot of us spend a lot of effort trying to avoid sugar in our daily diets, it still takes on ceremonial importance,” says Janes. “We still like to celebrate life with something sweet.”

So, go ahead and take that second piece of holiday pie. You can now rationalize that there’s a history lesson in it.