Race at the Center

Trayvon Martin. Michael Brown. Ferguson. Baltimore. Alton Sterling. Chicago. Black Lives Matter. Freddie Gray. Charlotte. Dallas. Philando Castile. Baton Rouge. Terence Crutcher. Tamir Rice.

The steady, mournful drumbeat of racial unrest, senseless death and reactionary violence reverberates across our nation. Through social media, the Internet and other vehicles, details of each tragedy send shock waves into every corner of America – even the serene West Michigan enclave of Hope College. At the bi-monthly meeting of Hope’s 80-member Black Student Union (BSU), “We have conversations about getting ready for grad school,” says organization president Curissa Sutherland-Smith, “but we also have conversations about things going on in the world.”

On a campus where U.S. minorities make up 15 percent of the student population and African American just 2.5 percent, such conversations easily could be lost in a vacuum. Words seldom carry lingering impact or historical context, or convey the direct link between modern-day outrages and atrocities of the past. As Vanessa Greene, director of Hope’s Center for Diversity and Inclusion, puts it, “The Jim Crow history is not talked about a lot in our society. We kind of go from slavery to Martin Luther King to President Obama.”

So perhaps the only thing more surprising than Hope approving Greene’s recommendation to present the exhibit “Hateful Things,” centering around a collection of blatantly racist images and artifacts from America’s Jim Crow era (1877 to as late as the mid-1960s), was the campus-wide, interdepartmental willingness to use the display as a springboard for discussion and education.

“Hateful Things” was paired with a second exhibit, “Resilience.” Both ran from Aug. 26 (just in time to greet students arriving for the fall semester) through Oct. 7 in the De Pree Art Center and Gallery. Nearly three years in the making, “Hateful Things|Resilience” emerged as the first dual exhibition in the gallery’s history.

“Hateful Things” is a traveling 39-piece sample from the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University in Big Rapids. It features multiple uses of the “N-word,” images of lynching, round black infants advertised as “alligator bait,” and more. It is equal parts fascinating and repulsive.

The Jim Crow museum, curated by Ferris State Vice President for Diversity and Inclusion David Pilgrim, is billed as the largest public collection of segregation-era artifacts anywhere. It is “all about teaching, not a shrine to racism,” Pilgrim, who is black, says on the museum website.

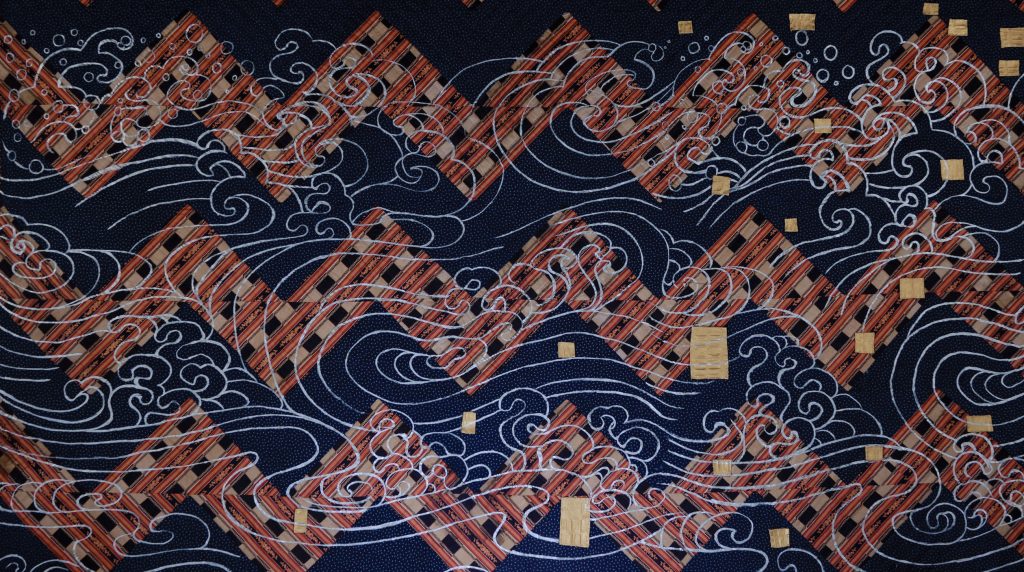

“Resilience,” curated by De Pree gallery director and Hope assistant professor of art Dr. Heidi Kraus, was a smaller exhibit showcasing colorful, hopeful works of such world-renowned contemporary African American artists as Sanford Biggers, Faith Ringgold and Lorna Simpson. With artwork on loan from the Monique Meloche Gallery in Chicago and Hope’s Kruizenga Art Museum, “Resilience” represented the first time “Hateful Things” was shown in conjunction with another exhibit.

“We had a wall, both metaphorically and physically, dividing the space,” Kraus says. “But when you were in the ‘Resilience’ portion, you could still see aspects of the other side. The individual artists in ‘Resilience’ may have not been directly responding to it (‘Hateful Things’), but it’s part of who they are and they’re aware of it. You can’t escape it.”

Greene had been aware of Pilgrim’s Jim Crow Museum for at least a decade. However, when she returned to the Ferris State campus several years ago for a conference, she scarcely could believe her eyes: the museum had moved from a single room to a gleaming, expanded space displaying more than 9,000 objects from its collection.

“When I walked in and saw all those dehumanizing items of African Americans, it just floored me,” she recalls. “Nine thousand artifacts, it’s just overwhelming.”

That planted the seed for Greene to inquire about the traveling “Hateful Things” exhibit. “I saw it as a way to live out Dr. Pilgrim’s vision to experience these painful images head on and process how they have shaped our society from a superiority-inferiority framework,” she says.

“But I was kind of afraid. I didn’t know what students would do or what the response might be, so I sat on it. Ultimately I decided the opportunities to educate our students far outweighed the fear of negative behavior or reaction from them.”

Greene approached Kraus with the idea. “I was like, ‘Vanessa I am pre-tenure. What are you trying to do to me?’” Kraus says, laughing. Then Kraus visited the Big Rapids museum and came away similarly determined. “But I knew very early on that this was going to have to have a lot of institutional buy-in here,” she says. “So immediately I started reaching out to people.”

Among many others campuswide, Kraus forged alliances with Dr. Charles Green, professor of psychology; Dr. Patrice Rankine, former dean for the arts and humanities, and his successor, interim dean Dr. Marc Baer; and Dr. Jeanne Petit, professor of history and department chair. “Heidi was very proactive about pulling in the entire academic community to make sure this exhibit went well,” Petit observes.

“There were very deliberate ties to the classroom to discuss, discuss, discuss, to make sure that the exhibit was seen in its proper context and not just put out there,” she says. “I think it was a great example of an ultimate goal of the college, to see things from multiple angles and gain a deep understanding of what a cross-disciplinary perspective can bring.”

First, however, Baer says the college did some groundwork for the show. “There were advance articles in the Anchor,” he says, “and select groups were invited to see it, then communicate back to their networks ‘This is what it is, and this is what it isn’t,’ particularly for minority students.”

Dr. Trygve Johnson, who is the Hinga-Boersma Dean of the Chapel, noted that communities grounded in faith such as Hope are particularly called to engage with society’s greatest challenges.

“The Christian does not hide or ignore the brokenness and darkness of the world; instead the call of the Christian is to see it, and name it as such,” he said. “‘Hateful Things’ is an exhibit designed for our community to name this brokenness and darkness of our racial past and present.”

“I hope the biggest takeaway is that the level of consciousness is increased so when people are making decisions or comments related to diversity and inclusion, this experience will register. I also want people to go to the core of their faith, their profession of faith. What does God call us to do?”

“Hateful Things|Resilience” served as the impetus for a series of related events across Hope’s campus. They included:

- A screening of the film From Jim Crow to Barack Obama, followed by a discussion with the filmmaker, Denise Ward-Brown, associate professor at Washington University in St. Louis

- A performance of the Randy Wyatt play A Simple Question by the Grand Rapids theater company Ebony Road Players, co-sponsored by the departments of English, History, Theater, and Women and Gender Studies

- “‘The Most Laughable Things I Had Ever Seen:’ Currier & Ives’ Darktown Comics,” a lecture by Dr. Marcy Sacks, professor of African American history at Albion College

- The presentation “The Roots of Economic Inequality: Race, Class and the Denial of the Past,” led by historian Dr. Anna-Lisa Cox ’94 of Western Michigan University, part of this year’s Critical Issues Symposium on “Economic Inequality in a Democratic Society”

- The Fall Arts and Humanities Symposium, “Am I Not Human? Racial Identities in Modern America,” featuring presentations from professors Dr. Kenneth Goings of Ohio State University and Dr. Leonard Harris of Purdue University, assistant professor Dr. Rachel Stephens of the University of Alabama, and Hope faculty members Dr. Jack Mulder ’00, Dr. Kendra Parker and Green.

Kraus says BSU president Sutherland-Smith, a junior psychology major from Chicago, came up with “Resilience” for the second section of the exhibit. Over dinner, Kraus confessed to her that viewing the Ferris State exhibit made her feel unclean, and guilt-ridden over white privilege. “I said, ‘Dr. Kraus, do you know why your exhibit means so much? Because it reminds us our ancestors made it through. Even during the Jim Crow era we were inventing things, doing things. We had resilience.’”

The question, Sutherland-Smith says, is “What do we do next? This is a subject we can’t let drop now because the exhibit is over.”

Those next steps can take many forms. In October, for example, a group of students organized a public awareness effort regarding Halloween costumes, some of which potentially can be offensive to African Americans.

“When we know better, we do better,” Vanessa Greene echoes. “I hope the biggest takeaway is that the level of consciousness is increased so when people are making decisions or comments related to diversity and inclusion, this experience will register. I also want people to go to the core of their faith, their profession of faith. What does God call us to do?”

It did not go unnoticed that the “Hateful Things|Resilience” exhibit was contemporaneous with the grand opening of the landmark Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. “I wish I could say I planned that,” says Kraus. “But it just shows that so many things around this issue are converging at the same time. This has been a blessing to me.”

Photo by Jon Lundstrom