Journeys through Hope: History and Memoir

Three decades apart, each possessing a passion for ministry when options for women were limited, a mother and daughter attended a Hope that was both of its times and offered skills and encouragement for moving beyond them.

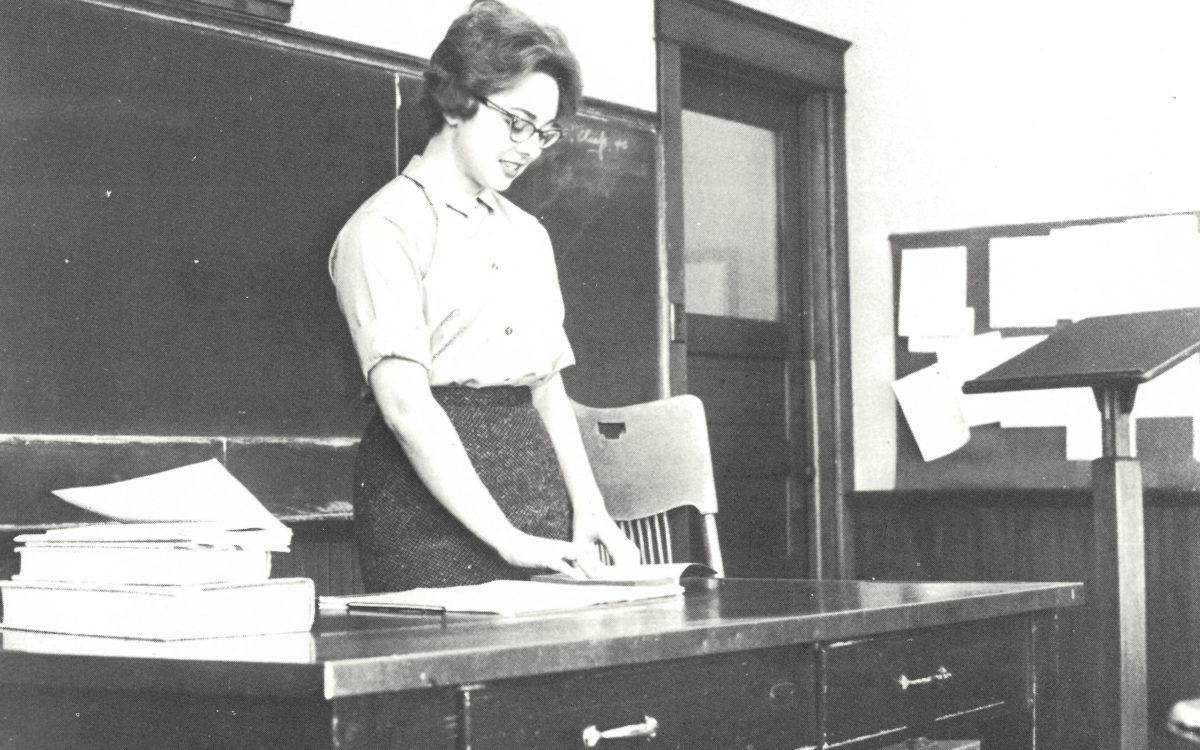

It was 1962. My Hope College Old Testament professor, the Rev. Dr. Simon DeVries, had asked me to come into his office. Yikes! Had I done something wrong? I loved the class, had gotten A’s on tests and papers, and had eagerly searched out extra reading. Daughter and granddaughter of Reformed Church ministers, accustomed to theological discussions in church, Sunday School and Catechism class, and at our family dinner table, I was fascinated, as Prof. DeVries taught us how to use history, archeology, sociology and literary criticism to understand God’s word. In his office that day, Prof. DeVries began, “You’re very good at this scholarship.” My heart swelled. High praise from this demanding, scholarly man.

And then he said, “You might think of becoming a director of religious education.”

Wait. Not a minister? Not a seminary professor? Nope. It would be 17 more years before the RCA ordained women. There were virtually no women seminary professors anywhere. Prof. De Vries, in the fine tradition of Hope faculty, was identifying and encouraging his most talented students, but DRE was all he could realistically offer me.

So, I majored in English, got a superb education at Hope College, got my doctorate, and became a college faculty member. I conducted research on how students learn to think and write in various college disciplines. In 2008 I published a study of how students developed intellectually and spiritually in 66 introductory religion courses around the country, including at Hope. The book helps teachers of religion courses understand their students and shape their teaching methods. That’s a kind of ministry, and Hope College gave me the skills to pursue it.

Let’s go back a generation. In the 1930s, among Hope’s 400 students were my father, Christian Walvoord, son of a Reformed Church minister and headed for the ministry himself, and my mother, Marie Verduin, from a farm family in South Holland, Illinois, who had all the qualities of an excellent minister.

The society and the college were VERY sexist. There were no women administrators (except dean of women) or board members. My father was elected president of his class, a position held only by men; my mother was elected secretary, a position held only by women.

The Anchor called women students “girls” and “little coeds.” Virtually all chapel speakers were men. Most education students were women, but the Michigan Educational Association meeting in Detroit in 1931 featured six “men of distinction” as speakers, no women. There were no women’s intercollegiate sports. There was an honor society for men but not for women. Cruel humor in The Anchor diminished women. I could go on.

But Hope offered women significant support for ministry, broadly understood.

In 1934, women constituted one third of the Hope faculty (nine of 27). Full professors were 13 men and 2 women. Women were limited to English, history, music, speech, drama and languages. Nonetheless, Metta Ross, Winifred Durfee, Laura Boyd, Shirley Payne and Nella Meyer were models of strong, capable women.

Many extra-curricular activities were gender-specific, so women gained speaking and writing skills in the women’s division of oratory and leadership experience as officers of the women’s sororities and the Young Women’s Christian Association.

To serve surrounding small churches, Hope sent out women’s as well as men’s student “gospel teams” to lead worship and youth activities. One team of women students drove 30 miles through a snow storm to South Haven, to lead a union service of three local churches, including offering the main address. The Anchor used “devotions” to name the woman’s address and “sermon” to name the address by a male student in a different church. Nonetheless, a woman got to be the main speaker for a church service.

With these kinds of support from Hope, my mother, after college, became a prominent leader in the RCA, helping to restructure the women’s organizations into a more unified and powerful force, and advocating for women’s ordination. She and three men received Distinguished Alumni Awards from the Hope College Alumni Association in 1975.

Another support for women in ministry was preparation of women missionaries. The Student Volunteers club supported those heading for the mission field. The majority of its members were women. Three Hope women students and one man joined 3,000 other college students at the national convention in 1931. All the speakers were men.

In 1930, Hope had 59 alumni who were missionaries, almost a third of them women, reported The Anchor — under the headline “Hope Men in Mission”! Hope gave women skills for the expanded roles they could fulfill on the mission field. At Hope, in 1920, Tena Holkeboer won first place in the women’s division of the Michigan Oratorical League. As a missionary in China, she directed four Chinese schools serving two thousand boys and girls. At Hope, all religion faculty and virtually all chapel speakers were men, but in the Philippines, Holkeboer taught Bible, presented chapel talks and led radio evangelism. (For an impressive study of women at Hope in the 1930s and 1940s by three Hope student researchers, see the Hope College Digital Project Archive at hopedla.org.)

And now? As just one example — and one who has an important impact on students today: Lynn Japinga, who graduated from Hope 18 years after me, in 1981. She went on for her M. Div. from Princeton Theological Seminary, became an ordained RCA minister and earned her Ph.D. from Union Seminary. She taught at Western Seminary. She served as pastor of RCA congregations. She is now the Rev. Dr. Lynn Japinga, Hope College professor of religion and author of five books. She has a broader scope for her talents, but in another way, she belongs to a long line of women who, despite the sexism of the college and society, found support at Hope College.

For more information on women at Hope, see Women’s Rights in Midwest Dutch America, 1847-1979: A History and Memoir (Wit & Intellect Publishing, 2023), available on Amazon.