Who was A.J. Muste?

Tell me you’ve heard of him: Abraham Johannes Muste (1885-1967), labor leader, world-renowned pacifist and probably Hope’s most famous alumnus.

Born in the Netherlands, Muste immigrated to Grand Rapids with his family in 1891; he graduated from Hope College in 1905, valedictorian, captain of the basketball team, president of his fraternity (the Fraters, of course), and already an acclaimed orator. He studied at New Brunswick Seminary and was ordained as a pastor in the Reformed Church in America in 1909. He served the Fort Washington Collegiate Church in New York City (close to Union Seminary, where he continued his education), but found himself increasingly uncomfortable with the doctrines of Calvinism and moved on to a Congregational Church near Boston. The year 1917, when the United States declared war on Germany, was a dramatic watershed for the young man: Despite social pressures around him, he adopted a position of radical pacifism.

Labor Leader

Pacifist

Hope Alum

Muste had already joined over 60 fellow pacifists to found the American wing of the international Fellowship of Reconciliation, and abandoning his pulpit he turned toward labor organization as a theater where his commitment to issues of peace and justice could find expression. In 1921, he became educational director of the Brookwood Labor College in New York and laid foundations for the Conference for Progressive Labor Action. Frustrated with the church, he was drawn for a time to communism, even visiting the noted Marxist Leon Trotsky in 1936. “What could one say to the unemployed and the unorganized who were betrayed and shot down when they protested,” he asked himself. “What did one point out to them? Well, not the Church… you saw that it was the radicals, the Left-wingers, the people who had adopted some form of Marxian philosophy, who were doing something about the situation.”

And yet A.J. didn’t have it in him to stay away from Christianity for very long. That same year he wandered into the Church of St. Sulpice in Paris and experienced a reconversion. “Without the slightest premonition of what was going to happen, I was saying to myself: ‘This is where you belong.’” On his return to the United States, Muste headed the Presbyterian Labor Temple in New York and then became executive secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation. In 1949, a very young Martin Luther King, Jr., then at student at Crozer Seminary, heard Muste lecture on non-violent resistance: it is fair to say that King would not have achieved his ambitions had he not had Muste as an example. [See sidebar on next page for what King wrote about Muste.]

In his years of “retirement,” Muste was more vigorous than ever, participating in a string of activities: the Polaris Action anti-nuclear protest; the anti-nuclear walk to Mead Air Force Base, where the 75-year-old climbed over the fence into the grounds; the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace; the Quebec-Guantanamo Peace Walk; the Nashville-Washington Walk; and the Sahara Project to oppose nuclear testing in Africa. In 1966, in the heat of the Vietnam War, he led a group to Saigon, where he was immediately deported, but shortly thereafter flew to Hanoi to meet Ho Chi Minh. Less than a month later, Muste died of an aneurysm. The great American linguist, philosopher and social critic Noam Chomsky has called Muste “one of the most significant 20th-century figures, an unsung hero.”

During the summer of 2017, I had the great privilege of accompanying prize-winning film-maker David Schock on a series of cross-country trips to interview and record the memories of people who knew A.J. or had written about him. It was an unforgettable experience, and the footage — nearly 40 feet of it now — is priceless. We heard the stories — often expressed in tears — of working with Muste, observing his deft administration and wondering at his dedication. What is the cost of a life like Muste’s, a life that so realizes the imitatio Christi? Surely Muste paid a price: his family’s finances were chronically precarious, he was often away from home and he endured the suspicion of many with whom he had grown up. One person we interviewed estimated that Muste had probably owned no more than four suits in his entire life, and his shoes often revealed patches in the soles. Yet Muste was a happy man. I love this story from his co-worker Barbara Deming, who was with him when he was arrested in Vietnam. “None of us had any idea how rough they might be,” she recalled, “and A.J. looked so very frail…” “I looked across the room at A.J. to see how he was doing,” she went on. “He looked back with a sparkling smile and with that sudden light in his eyes which so many of his friends will remember, he said, ‘It’s a good life!’”

Muste wasn’t an English major. But he loved poetry, and it inspired him. One of his favorites was “The Hound of Heaven,” by Francis Thompson:

“I fled Him, down the nights and down the days;

I fled Him, down the arches of the years;

I fled Him, down the labyrinthine ways

Of my own mind, and in the mist of tears…”

And this one, which was read at his memorial service, Stephen Spender’s “The Truly Great”:

“I think continually of those who were truly great.

Who, from the womb, remembered the soul’s history

Through corridors of life, where the hours are suns,

Endless and singing.”

![]()

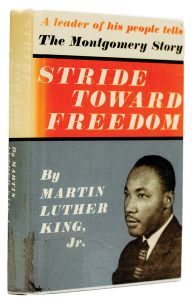

Muste and King

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was among those inspired by A.J. Muste. King was a student in the audience when Muste spoke at Crozer Theological Seminary in 1949, and later recalled the encounter’s significance in his book Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story.

Writing in the chapter “Pilgrimage to Nonviolence,” King said, “During my stay at Crozer, I was also exposed for the first time to the pacifist position in a lecture by Dr. A.J. Muste. I was deeply moved by Dr. Muste’s talk, but far from convinced of the practicability of his position.” (King went on to explain that his subsequent study of Gandhi revised his view on the viability: “It was in [the] Gandhian emphasis on love and nonviolence that I discovered the method for social reform that I had been seeking for so many months.”)

King and Muste — who has been called “the American Gandhi” — remained in contact through the years. They corresponded in the 1950s and 1960s, and King was the featured speaker during a 1959 War Resisters League dinner held to honor Muste. Following Muste’s death, King noted, “the whole world should mourn the death of this peacemaker, for we desperately need his sane and sober spirit in our time.”

![]()

Remembered on Campus

A commissioned bust installed at Hope this fall adds a new dimension to a space that has quietly honored A.J. Muste for more than 30 years.

Dedicated on Nov. 13, the bust and a plaque with a biographical sketch have been placed in the A.J. Muste Alcove on the second floor of the Van Wylen Library. The study alcove was named in 1988, the year that the library opened, and was labeled with signs but lacked information about him.

The effort to have the bust created — and to increase campus awareness of Muste and his work — was led by Dr. Jonathan Cox ’67, who is retired from Hope as the DuMez Professor Emeritus of English. It was sculpted by Dr. Ryan Dodde ’89, who is a plastic surgeon in Holland, Michigan, and had been recommended for the project by the late Billy Mayer of the Hope art faculty.

The dedication followed other recent remembrances that included a panel discussion about Muste in November 2017, which helped mark the 50th year since his death; a historical display at the library in the fall of 2017; and a lecture in March 2018 by Dr. Leilah Danielson, author of American Gandhi: A.J. Muste and the History of Radicalism in the Twentieth Century.

Muste is being honored this spring through an even longer-standing commemorative event: the annual A.J. Muste Memorial Lecture series, established in 1985. This year’s lecture, “What Would A.J. Muste Do Today?” will be delivered on April 17 by Mary Neznek ’70, who is an award-winning disabilities advocate and lobbyist working on nonviolent conflict resolution positions in Middle East conflict zones. In addition, the documentary A.J. Muste: Radical for Peace/Finding True North by filmmaker David Schock will be shown in advance of the lecture, on Tuesday, April 16.

![]()

News from Hope College had been planning for about a year to develop a story about A.J. Muste for this issue, occasioned by the dedication of the bust discussed elsewhere on these pages, when we saw an article about him by Dr. Kathleen Verduin ’65 of the English faculty on her department’s blog this past fall. We immediately sought to reprint it, not only because we appreciated the high quality of her writing but because she has a unique and informed perspective as chair of the college’s A.J. Muste Memorial Lecture Committee. The latter role and her faculty status also provided an irresistible parallel. A story about Muste that was in this magazine in April 1985 was written by the committee’s first chair, biologist Dr. Donald Cronkite, who had been a leader in building campus and local awareness of Muste’s work.