Research on the Dynamic between Faith and Mental Disorder

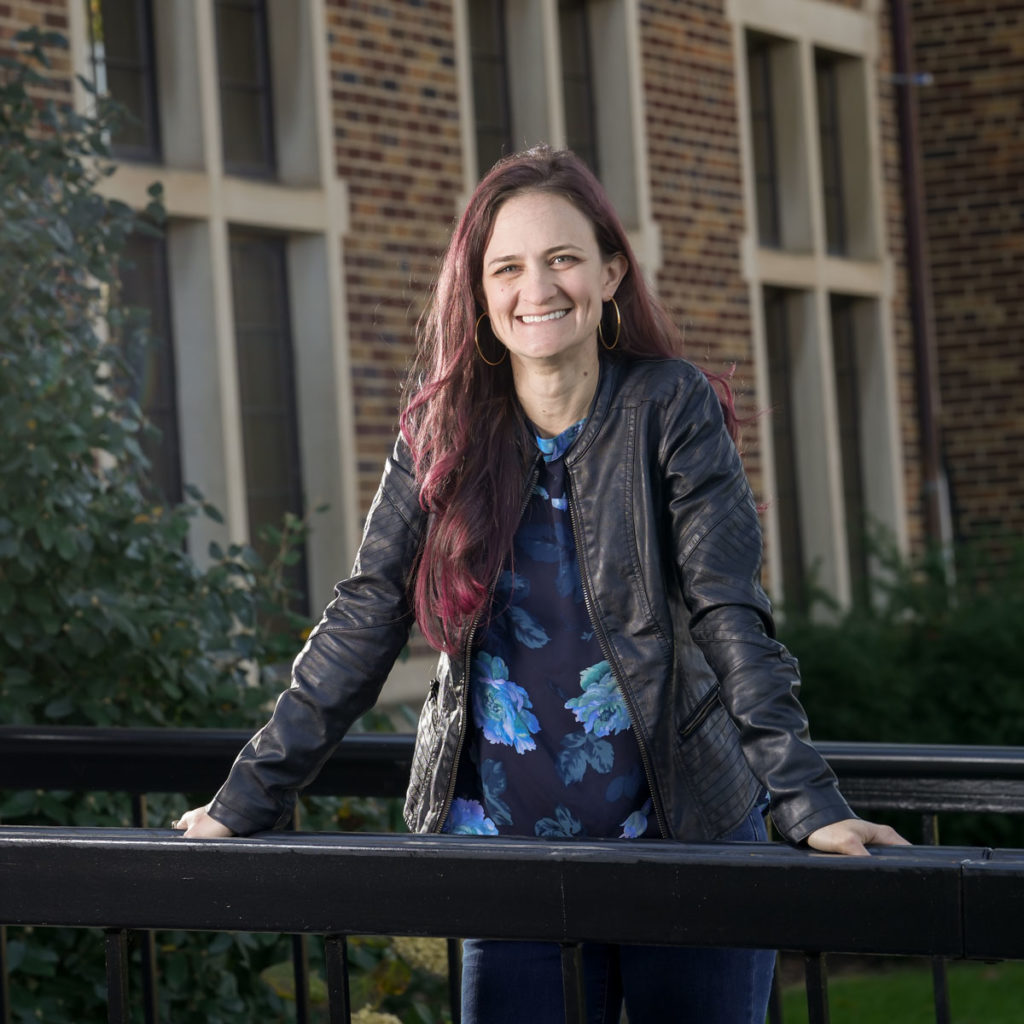

Dr. Kate Finley

Let’s begin by telling you what Hope Assistant Professor of Philosophy Dr. Kate Finley is NOT trying to prove in her research:

RESOLVED: If you believe in God or have faith in Christianity, you must have some sort of mental disorder.

No, what’s driving her research efforts these days are the interactions and intersections between various types of mental disorder — such as bipolar disorder, depression and schizophrenia — and different facets of religious beliefs and experiences. And in part because so little has been written on that connection from a philosophical standpoint, Finley has received for this project over $150,000 in grant funding through the University of St. Andrews, Fuller Theological Seminary, Blueprint 1543, Calvin University (all funded by the John Templeton Foundation) and from the Hope College Global Health Program.

For a philosophy professor to win an outside research grant is something akin to you hitting the jackpot.

“Even though it’s not much compared to people in the sciences, these smaller research grants, including Hope’s summer Nyenhuis research grants, have been incredibly helpful in me getting this project going,” says Finley.

Finley says she became interested in the subject through her own experience; the experiences of loved ones; her volunteer ministry experience with children, adolescents and adults; and her experience teaching inmates at the Richard A. Handlon Correctional Facility in Ionia, Michigan. “Mental disorder is a topic that comes up over and over again,” she says. “It’s a real point of struggle for a lot of people. And for people who are religious, understanding how mental disorder interacts with faith is an important part of that.”

Over the course of this project, her research team has conducted lengthy interviews with over 70 participants, and questionnaires with over 260 participants who identified as having a mental disorder and also having significant experience with Christianity. “We did not just focus on people who currently identified as Christian, but also participants who said, ‘I’ve gone to church in the past, I used to be a Christian, but partially because of how it treated mental disorders I have left the faith,’” Finley says. “It’s really important to include the perspectives of those people.”

She sought out a wide age range, including Hope undergraduates, “because people at different points in life have really different perspectives on how their mental health and religious identity impact each other. But obviously, for adolescents and young adults, mental health is one of the biggest concerns right now.”

Much has been written on this subject by psychologists and some by theologians, “but I was surprised to find out that only one philosopher had written on this previously,” says Finley. “One of the gaps I saw that really interested me was the potential positive and meaningful effects of mental disorder on religious beliefs and practices. There has been a lot written on the negative effects mental disorder and religion have on each other, and a lot on the positive ways that religion can help people cope with mental disorder, but I was really interested in the opposite direction.”

Perhaps you should expand on that, Doctor. “Just to be clear, by positive or meaningful effects of mental disorder on religion I don’t mean that the disorder is positive — that it doesn’t cause suffering, or that God gave someone their disorder. I just mean that one of the key ways we deal with suffering of any kind is by finding some kind of deeper meaning in it, and religious meaning is often a big part of that. That was missing in work on mental disorder, and it’s really important to fill in that gap because without frameworks for finding religious meaning in mental disorder it can be incredibly difficult to do without slipping into ‘over-spiritualizing’ mental disorder and ignoring the biological, psychological and social aspects.

“Some people that we interviewed said some version of ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about, when you ask about positive effects of mental disorder.’ Although some people may never experience positive meaning from their mental disorder (through no fault of their own), in these statements some participants seemed to indicate that there was a lack of conceptual space for them to even entertain the possibility of positive meaning. And as a philosopher, I’m all about conceptual space and conceptual frameworks.”

On the other hand, “I hoped we would find people who had drawn some positive meaning from their experiences and suffering, but I was surprised by how many people did,” she says. “I found it really fascinating that people talked about how their experiences with mental disorder challenged and ultimately changed their idea of faith and God’s character and purpose for us. But there are also obviously people whose experiences with mental disorders have undermined their faith. I’m really grateful and truly humbled that so many people have shared really vulnerable details about their lives in the interviews that they’ve given.”

Finley says this research will continue for at least a couple more years. “I have plenty of ideas I still want to work on and studies I want to run,” she explains. She’s also collaborating on several related projects with teams of neuroscientists and psychologists, with funding from Duke University, to study the neurological dimensions of some of these topics — especially stigma towards those who experience psychotic disorders, and the role of firsthand narratives in shifting this stigma.

In the research she conducted this summer, Finley worked with Dr. Stephanie Pangborn of the communication faculty as well as students Christina Chiazza ’23, Brooke Bennett ’24, Emmelyn Simpson ’24 and Emily Davidson ’24. Chiazza, Bennett and Simpson continued to work with her this fall. Bennett was so inspired by the experience that she is attempting to form a student-based group to discuss the intersections of religion and mental health at a grassroots level.

Finley encouraged the student researchers to pursue their own projects inspired by the assignment.

“[O]ne of the key ways we deal with suffering of any kind is by finding some kind of deeper meaning in it, and religious meaning is often a big part of that. That was missing in work on mental disorder.”

“I plan on going into clinical psychology, so I was less interested in writing a paper than in some of the practical applications of our research,” says Bennett, a psychology and global health double major. “On campus there are resources relating to mental health, but one thing our campus is lacking is peer support. Often people feel reluctant to seek professional help. I believe a peer group could be a great bridge for people to be more comfortable using more professional resources.”

When she isn’t exploring the rational investigation of the philosophy of mind and cognitive science, Finley pursues her passion as a visual artist. Does she have a favorite medium?

“I totally didn’t expect that question,” she says, smiling. “I was originally an art major in college. I mostly work in oil and watercolor paint, but recently I’ve gotten into some digital stuff — pretty rudimentary coding and interactive designs.

“I’m interested in art both as an artist and from a philosophical perspective. I think there are actually some really interesting tie-ins to the mental disorder and religion research, because art can communicate in non-literal, often metaphorical, ways, and those things can transform our thinking in a pretty distinct way.”

Finley notes that “for example, art can shape our theological conceptions. Artwork that presents God as being separate or distant from us, or as having a particular race or gender — those things can become deeply entrenched in how we think of God, often without us realizing it. So it’s important to acknowledge and utilize these influences, and in some cases, challenge them.”