A Honey of a Project

It takes eight to 12 bees a lifetime to produce enough honey to fill a single teaspoon.

The three hives installed on the Hope campus this past spring generated 10 gallons that ultimately found their way to the shelves of the college’s bookstore to provide a sweet taste of campus and West Michigan.

That’s a lot of bees doing a lot of work.

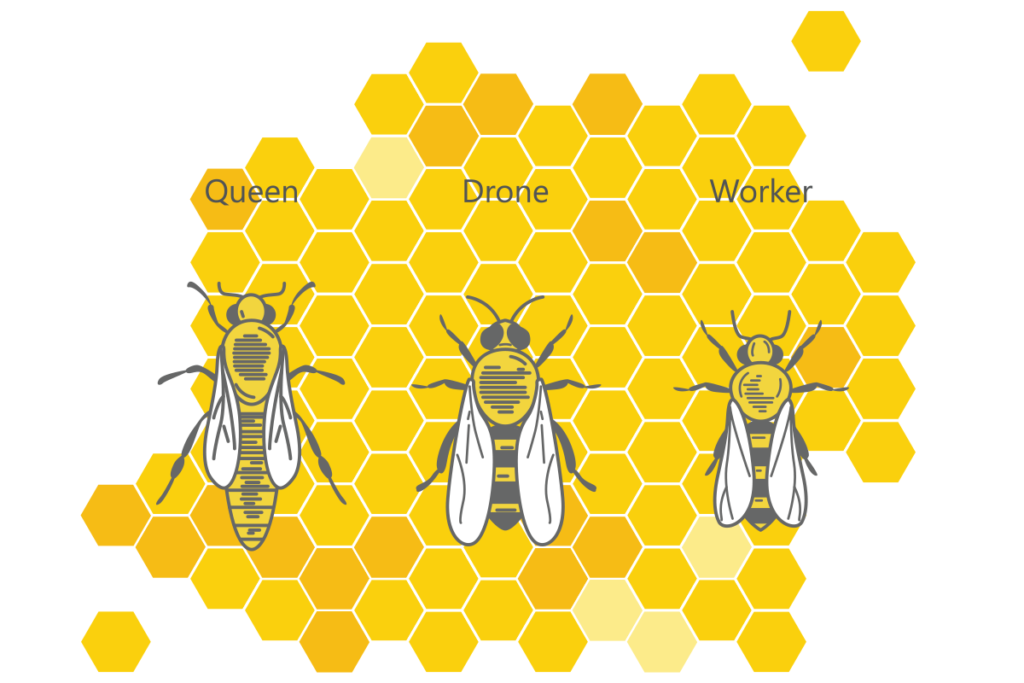

The busy insects — which can journey 3-5 miles away in their quest for nectar and pollen — have joined the Hope community through a team effort by the college’s Office of Sustainability, grounds department, environmental sciences program and Creative Dining Services (Creative). The honey is a bonus. The goal is to provide local action to help address a global issue: the decline of pollinators essential to crops such as fruits, nuts and many vegetables, and — by extension — the world’s food supply.

Honey bees are a very sensitive population. They’ve been having a really hard time with pesticides and herbicides, and that’s decreased the population.”

It’s not just honey bees that are at risk, but other pollinating species like bats and hummingbirds. The United Nations considers it enough of a crisis that it has even designated May 20 as “World Bee Day” to bring attention to the issue. As explained by the UN, “Close to 35 percent of invertebrate pollinators, particularly bees and butterflies, and about 17 percent of vertebrate pollinators, such as bats, face extinction globally.”

Gibbs noted that she and Hope’s grounds manager, Bob Hunt, had discussed the idea of adding an apiary to campus for some years, with resources and others’ enthusiasm and knowledge coming together this year to bring the project to fruition. The resources — underwriting the purchase of the bees, hives and related equipment — included a grant from Creative, which provides food service for campus and operates Hope’s Haworth Hotel, and from the college’s revolving fund for sustainability projects, which accrues from a portion of the savings from previous efforts like the installation of energy-efficient lightbulbs on campus. The enthusiasm, knowledge and time have been contributed by friends of the college and members of the Hope family, many of whom were already involved in beekeeping.

The bee team is particularly grateful, she said, to Don Lam ’66 for providing expertise and, through his home-based business, Don Lam Bees, equipment and even bees. Lam and his wife, Jean, have been keeping bees for nearly 25 years, and Don is an officer and past president of the Holland Area Beekeepers’ Association, and serves on the board of directors for the Michigan Beekeepers’ Association.

“He’s been a great resource,” Gibbs said. “We’ve taken a lot of classes with him, he’s always helpful when we have questions.”

Among other lessons: Beekeeping requires patience, not least of all because colony survival isn’t guaranteed. Nationwide, a recent survey found that 40% of managed hives don’t survive the winter, with losses during the summer as well. Hope’s successful colony followed two attempts earlier in the year that failed.

The apiary has been placed in a quiet corner of the college’s athletic fields, well distant from where competitors and fans gather. That might seem like a precaution on behalf of Hope’s human denizens, but it’s actually for the bees, who are pretty mellow but simply do better with some privacy, early eastern sun and a nearby water source.

“These bees are not aggressive,” said Janine Oberstadt, who is assistant vice president of operations with Creative — and as a beekeeper herself is helping with the project. “Only if you’re really messing with them are they going to come after you. We have what I call ‘really sweet bees.’”

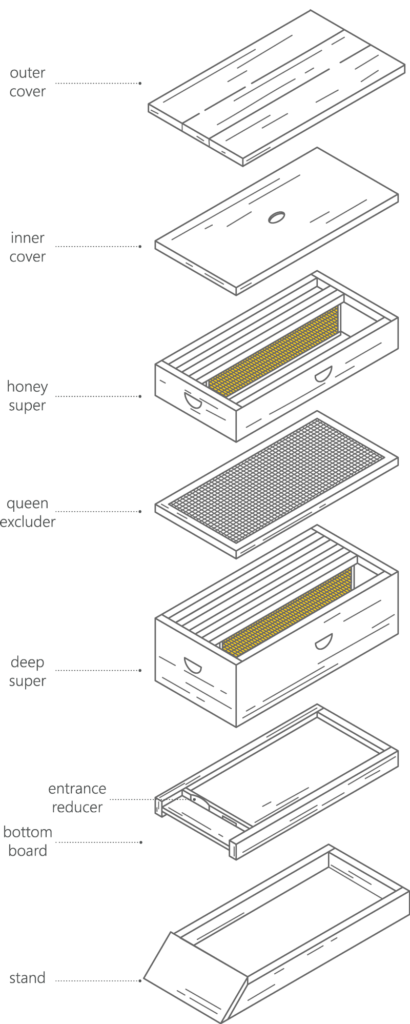

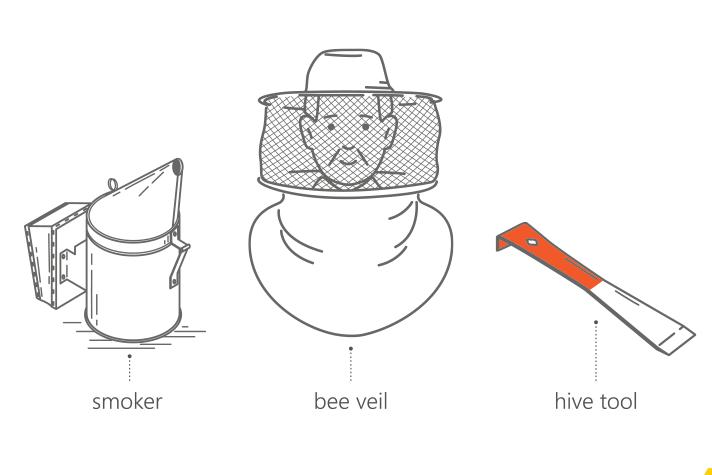

That assessment was borne out in the latter part of September, when Hope’s “Bee Team” collected honey-laden frames from the hives. On that particular day, Chef Jay Sharkey, who is a volunteer with the Hope project and a beekeeper with Creative, provided guidance. Corporate culinary training coordinator with Creative, Sharkey has a strong connection to Hope through his wife, Ann, who has been on staff at the college’s Haworth Hotel since it opened in 1997. He brought along a smoker to calm the bees if necessary, but they didn’t even seem to mind when he gently brushed them from the wooden frames that fill the hives and contain the honeycombs.

As for the frames themselves, Sharkey was pleased by the amount of honey that the bees have produced.

“I’m pretty happy we got something with first-year hives,” he said. “That’s very encouraging.”

The team is careful not to take too much. The bees, after all, have a reason for generating the honey.

“We’re very careful that we only take surplus honey — that’s an important part of the beekeeper’s job. Each hive needs 80 to 100 pounds to survive for the winter.”

By season’s end, the hives yielded 60 frames’ worth of surplus. The Bee Team next gathered in the certified kitchen in the college’s Cook Hall on October 10 to spin the honey, which is surprisingly literal. The process begins with scraping away the wax caps with which the bees have covered the hundreds of honey-filled hexagonal chambers in each frame. From there, the frames are lowered into cylindrical extractors that are essentially centrifuges. By hand crank or motor, they’re spun in a circle until the honey flies out of the honeycombs, drains down and can be collected from a faucet at the bottom.

The resulting 200 bottles — each containing eight ounces and custom-labeled for Hope — went on sale at the Hope College Bookstore on Oct. 21. The proceeds will be poured back into the college’s sustainability revolving fund and support new initiatives in the future.

The hives, in the meantime, have been carefully winterized (the bees will keep them a toasty 80-90 degrees) to give them the best chance to endure the season. Come spring, the cycle will begin anew.

The Hope-produced, 100%-raw honey is being sold at the Hope College Bookstore for $10.99 a bottle while supplies last.