What Makes Athletes Tick?

Students Team with a Sport Psychologist on Six Summer Projects

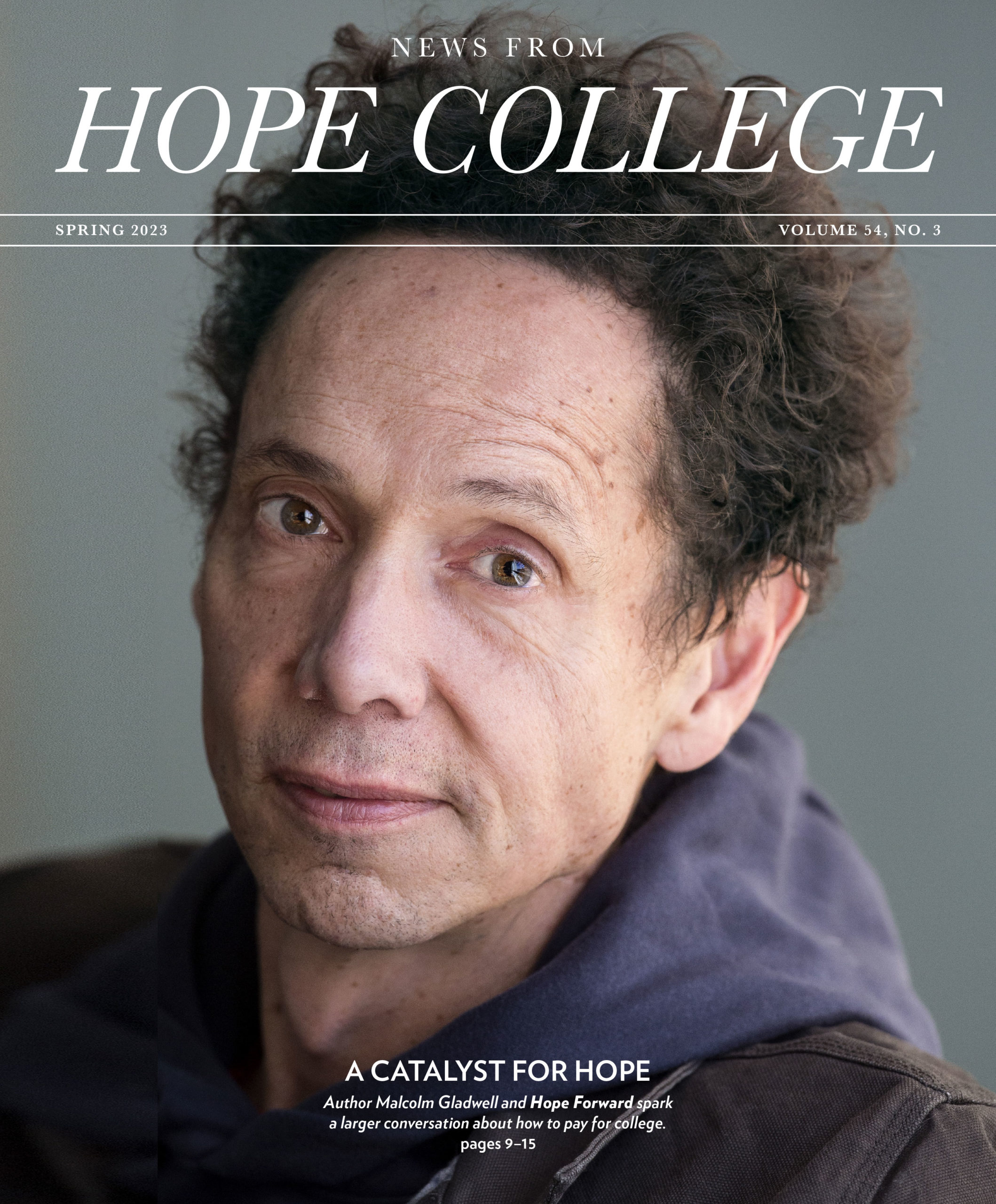

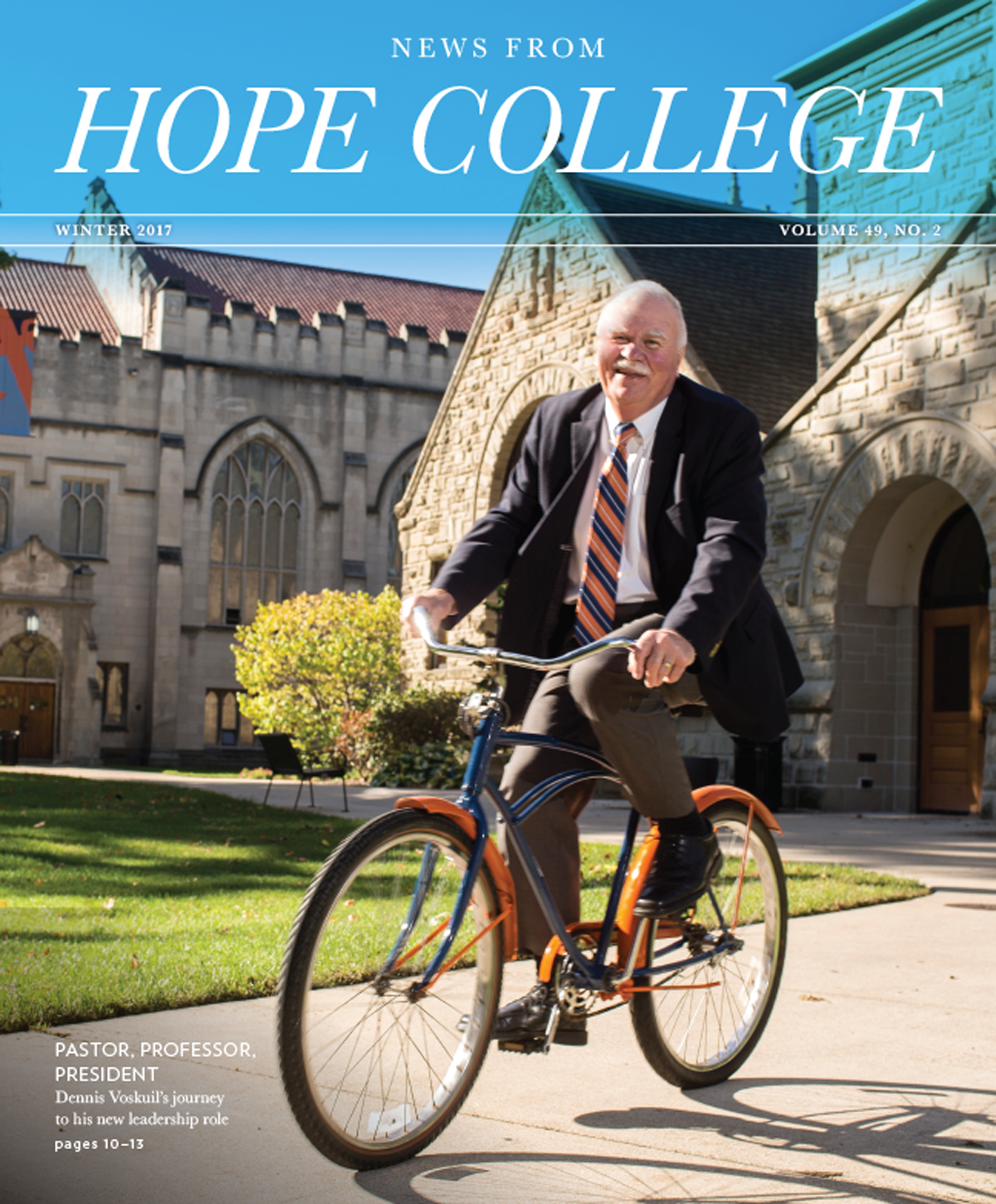

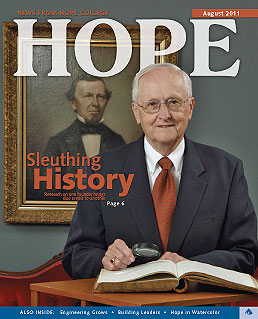

Dr. Femi Oluyedun

From the start, it’s been go, go, go for Assistant Professor of Kinesiology Dr. Femi Oluyedun. (Growing up with three brothers may have contributed to that lifestyle and mindset.) From a childhood immersed in sports to a stint on Wabash College’s soccer team as an undergraduate psychology major, through his years of study for his master’s degree and Ph.D. in psychosocial aspects of sport and physical activity, he’s long been fascinated by sports and the human behaviors around them.

“A big part of me getting interested in the field of kinesiology was based around my love for sports and background in studying psychology as an undergrad,” he said. “I eventually combined the two, and it has been such a fulfilling and enjoyable endeavor.” It’s been fun for his students, too, who experience the vast task of research projects — from warm-up to finish line — under Oluyedun’s coaching.

This summer, Oluyedun has some half a dozen projects on the go — some applied, others theoretical. They’re led by Hope kinesiology majors and psychology majors — student researchers getting an early taste for experimental and survey methods of learning about athletes’ minds and bodies, and how they work together on and off the court and field and pool. You could say he has a lot of balls in the air: It’s a balancing act he’s been training for his whole life. Oluyedun is coaching a scholarly team toward research prowess and academic sportsmanship.

It’s not uncommon for Oluyedun’s students to be drawn into applied kinesiology and psychology exercises with athletes — projects with practical goals — followed by immersion in the research world. Of at least one student, Oluyedun noted, “it’s been cool to be able to see how we’ve gone from her taking a few of my classes, to then working with her on how to do applied sport psychology — actually sitting down with groups of athletes and trying to teach them how to do different mental skills to improve their performance — to now, this summer, getting into the research side.”

Students develop their initial idea with deep dives into the literature to grasp their project’s theoretical angles, then propose the study for approval and obtain informed consent from participants before collecting data through a survey or an experiment. Ultimately, they analyze their data, write up their findings, and present them—sometimes at Hope, sometimes at conferences. (Two of Oluyedun’s student research partners recently made presentations at a regional conference hosted at Michigan State University, and another presented at a national conference.) The time-consuming but rewarding process prepares students to forge their own paths into careers in applied fields of physical therapy and medicine, or into research-focused graduate school programs.

“My goal is to help them see just how much time and effort it takes to do just one project,” Oluyedun said. “It often takes a minimum of a year, and it shows that you can’t skip any steps if you’re trying to complete quality work with the goal of publishing in a top journal.” Research is a long, patient game; it helps to have an experienced, patient coach.

One study led by several Hope swimmers is investigating whether the strength of a swimmer’s motivation varies with his or her role (starter or non-starter) on the team. Another group is researching the extent to which peer relationships influence athletes’ perfectionism and their “impression motivation behaviors” — their drive to come across well to others. Since athletes are routinely under the microscope, they may have elevated impression motivations. “We literally create these vast arenas to watch athletes perform in their sport,” Oluyedun said. “Well, we’d be interested to know to what extent athletes feel a need to constantly monitor their behaviors in order to fit in or be a strong role model.”

A third project this summer probes the relationship between levels of adipose (fat) tissue and student athletes’ working memory. Previous research indicates that students who exercise at the campus gym three or more times per week tend to have higher GPAs than those who do so less frequently. However, “it could very well be that the people who happen to go to the gym more often are also the people who happen to be high performers,” Oluyedun cautioned. “So this study would actually let us examine the direct connection between a physiological measurement, like adipose tissue, in tandem with cognitive ability (working memory).”

A student who’s a former baseball player is leading a study on the relationships within sleep and sport. That research group is aiming to collaborate with researchers in Hope’s Department of Psychology. “Does someone rate less anxiety if they report better sleep?” Oluyedun wondered. “That’d be an interesting question because we know that, for an athlete, you want to be able to reduce your anxiety and we know that you want to be able to enhance your sleep — to get the best quality sleep — if you’re trying to have the best performance.”

Oluyedun’s time and training encompass more than studies, however. He’s also involved with community workshops through ExploreHope Academic Outreach that demonstrate to high school students what the health professions look like — from practitioners’ perspectives. The 2022 workshop was the first to take place in person.

In this June’s health professions camp, Oluyedun led a day-long program on sport psychology. Some of his Department of Kinesiology colleagues led the days focused on exercise physiology and on anatomy. High school students walked away with a taste of professions that could, one day, become their own careers.

Oluyedun’s top academic coaching tip? Getting involved in research during the undergraduate experience may be the best move you ever make. “It can help you orient how you plan to go through your undergrad career, and it teaches different skills. I think it’s one of the most formative experiences you can have as an undergrad.”

Oluyedun’s top academic coaching tip?

Getting involved in research during the undergraduate experience may be the best move you ever make.

“It can help you orient how you plan to go through your undergrad career, and it teaches different skills. I think it’s one of the most formative experiences you can have as an undergrad.”