Generation Spark

To really wrap your mind around the work of Generation Spark, you first need to get a handle on the nones and the dones.

Let’s start with the “nones,” a term used in the media as a shorthand way to talk about those who identify themselves on surveys and polls as having no religious affiliation. In other words, they check the box that says “none.” Many of these nones are young people (age 16–24) who grew up in the church but didn’t stick around.

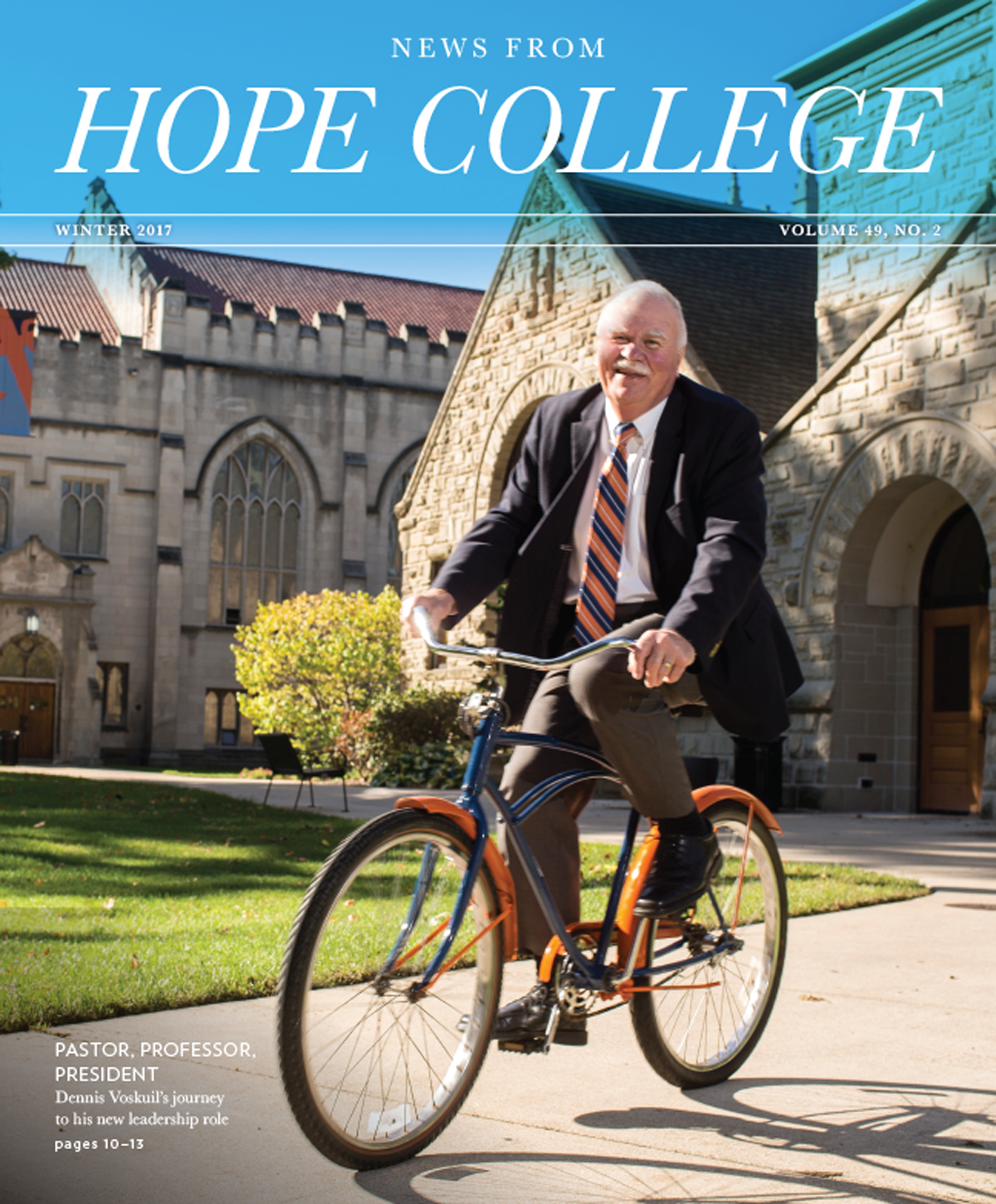

The “dones” is a term that’s far less common. Dones are people age 45 and older who, in the words of Virgil Gulker, director of Generation Spark and a lecturer for Hope College’s Center for Leadership, “have been in most cases pillars of the church, but they’ve grown weary of the institution.” They’re done.

The nones and the dones. Two vastly different age groups that present the same problem: After spending years in the church, people are leaving.

Generation Spark aims to do something about it.

Supported by a 2017 grant of $458,502 to the college from the Lilly Endowment Inc., this intergenerational mentoring program with a twist is currently being piloted in five churches in the Christian Reformed Church in North America and the Reformed Church in America denominations. (Additional denominations have already expressed interest in using the model.)

One year into the grant period and several months into the pilot program, five participating churches have brought church members from the nones generation and the dones generation into formal mentoring relationships, with each pair supported by a prayer partner.

The research-based idea behind this mentoring model is that by giving young people meaningful relationships with older adults — and giving older adults an opportunity to share their life experiences and influence the younger generation — each group could be an antidote to the other’s declining participation in church life.

That’s one of the reasons VictoryPoint Ministries in Holland, Michigan, got involved. “We were intrigued by the idea of the cross-generation relationship and how much these pairs could speak into each other’s lives for personal growth and for bridging gaps within our church community, leaving both feeling valued and cared for,” said Wendi Kapenga, director of the church’s Generation Spark program.

“Intergenerational mentoring is very popular right now,” Gulker said, “but the problem is that when you take a 60-year-old and put them with a 16-year-old, it’s just flat-out weird. They have nothing in common.”

The primary purpose is to create relationships where youth and older members come together and begin to explore life issues.

To help ease the potential awkwardness that comes with intergenerational relationships, the Generation Spark team took inspiration from a consultation model that the Center for Leadership has been successfully practicing for years, in which students are paired with an adult mentor to solve a problem in a local organization.

It’s here, in the combination of a mentoring relationship with a problem-solving purpose, that Generation Spark really shines.

The youth-and-mentor pairs in the pilot group have spent 12 weeks addressing practical issues in their own churches. Generation Spark has provided a list of project ideas, but each group instead developed its own ideas to pursue.

At VictoryPoint Ministries, 18-year-old Drew Deur was previously involved in weekly worship at Benjamin’s Hope, an intentional community in Holland, Michigan, that serves adults with autism and other developmental and intellectual differences. Together with his mentor, Tom Buursma, he worked to bring awareness about autism to VictoryPoint.

“Most of the church has a general understanding of what autism is, but they don’t know everything about the condition and the programs that exist to help the people it affects,” Deur explained. Together, Deur and Buursma researched and presented ways to connect their church with the ministry of Benjamin’s Hope, with the long-term aim of establishing a missional community to serve those with autism.

Casey Shannon is a 23-year-old at VictoryPoint who works full time as a machine operator and attends school part time. He and his mentor worked to create an online tool to build relationships among church members who, like Shannon, have schedules that don’t allow them to connect with the church’s regular Bible study sessions.

Faith Church in Zeeland, Michigan, became involved with Generation Spark when church leaders were approached by Matt VanDyken, a Hope College junior and member at Faith who was involved in launching the Generation Spark pilot program.

“It just fits with who we are as a congregation and with what we believe is absolutely necessary,” said Pastor Jonathan Elgersma.

The research-based idea behind Generation Spark’s mentoring model is that by:

giving young people meaningful relationships with older adults

and giving older adults an opportunity to share their life experiences and influence the younger generation

each group could be an antidote to the other’s declining participation in church life.

One project at Faith Church has taken the youth leadership question head-on. With help and encouragement from his mentor, a student attended a recent consistory meeting to present an idea about forming a youth leadership team that has a crossover conversation with the church’s governance.

“They didn’t say ‘We want to lead the church,’ but, ‘We want to learn with you about what it means to lead the church,’” Elgersma recalled. “Here we have a junior in high school doing the whole presentation in front of the consistory, and a great response from one of our elders was, ‘You had me at hello.’”

Other projects from the pilot group include exploring the feasibility of a church-based food bank and a community-based garden, promoting random acts of kindness within the church body, addressing the issues of suicide and self-harm among high school students in the community, and developing a structure for small groups based on special interests.

“It’s important to remember that problem-solving is merely the glue for the relationship,” Gulker said. “The primary purpose is to create relationships where youth and older members come together and begin to explore life issues.”

The measure of success, then, is not whether a team or a church implements a lasting solution for, say, housing pregnant teens (although that would be great). Rather, the measure of success is whether a church has developed thriving intergenerational relationships.

At VictoryPoint, each team has completed its project, but Kapenga is quick to point out that the projects “became secondary to the relationships that grew out of their consistent weekly meeting time.”

In a focus group, Gulker and his students asked young participants why they were part of Generation Spark. None of them said they were involved to solve the problem; instead, they showed up for the relationship.

“When we start thinking intentionally about the next generation, we’re thinking about ministry the way God thinks about ministry,” Elgersma noted, pointing to several biblical examples: Moses and Joshua, David and Solomon, Elijah and Elisha, Paul and Timothy, Jesus and the disciples, Elizabeth and Mary.

“Ultimately, we want this to be part of our culture here at Faith,” Elgersma said. “We’re not just talking about this as a program, we’re talking about this becoming part of our DNA.”

That’s about as perfect an outcome as Gulker could imagine. “I just hope God uses us to be one small step in that direction,” he said.