Delving Deep into Zebrafish Brains for Clues about the Sense of Smell and Adaptation to Climate Change

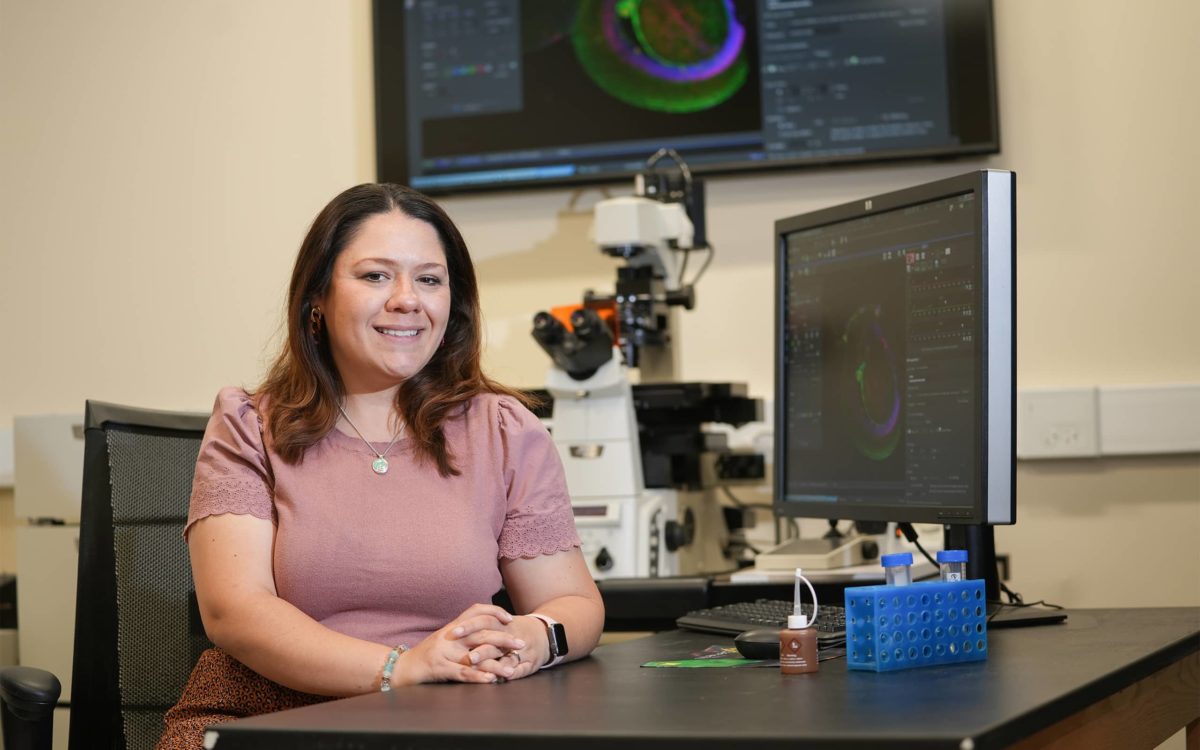

Dr. Erika Calvo-Ochoa

To Dr. Erika Calvo-Ochoa, science is about storytelling. Diminutive zebrafish, with their perpetually surprised expressions and uncannily keen sense of smell, are her striped protagonists. Small though they are, it’s their even tinier neurons that are the focus in Calvo-Ochoa’s laboratory. With student researchers, the molecular neuroscientist is studying olfaction and neural recovery in this species that does both rather better than humans can.

Zebrafish are heavily dependent on their olfaction (sense of smell) for everything from finding food and mates to avoiding predators. “There are a lot of new cells being born in the olfactory neurons in the nasal epithelium — or, to put it more simply, in the nose — just to cope with potential damage,” explains the assistant professor of biology and neuroscience. As the zebrafish brain is also continuously replacing cells, the whole olfactory system is adaptable. “It needs to be able to swiftly change in order to keep up with the environmental demands,” Calvo-Ochoa says, voicing her main hypothesis.

That hypothesis fuels three studies Calvo-Ochoa is conducting with her students. In the first, they impair the fish’s olfactory brain regions, and then over three weeks they observe physical structures and behavioral outcomes as the fish lose neurons and their corresponding sense of smell — and, fascinatingly, then regain them. “If we want to translate that into a human disease, it could be like blunt force trauma to the head and olfactory loss,” Calvo-Ochoa says, with the caveat that for humans, there is no natural neural recovery — yet. Research like Calvo-Ochoa’s dissects the capabilities of other species that may, one day, be replicable in humans.

“The idea is that, collectively, all of this knowledge will build up,” Calvo-Ochoa says, thereby paving the way for human applications.

Parkinson’s disease, for example, is often characterized early by a disrupted sense of smell. Dopamine, a molecule produced by the brain that conveys signals between neurons, is involved in many bodily functions — movement, memory, mood and sense of smell among them. While zebrafish are not susceptible to Parkinson’s, Calvo-Ochoa’s second project mimics this disruption by eliminating dopamine-producing neurons in the fish’s olfactory bulb (a structure at the tip of its long, narrow brain). The researchers introduce a drug that is structurally similar to a dopamine precursor chemical. The neurons are hoodwinked by the mimicry and absorb the drug to process into dopamine — only to be dispatched by the toxic compound. Only dopamine-producing neurons in the olfactory bulb are destroyed, leaving the rest of the brain purring along at full capacity.

“To me, zebrafish give the best of both worlds, because they’re similar to us,” says molecular neuroscientist Dr. Erika Calvo-Ochoa, noting that the species shares over 70% of its genes with humans. “They’re also different in the ways that mean we can learn so much from them.”

Because dopamine-producing neurons are the ones affected by Parkinson’s disease, studying the results of their demise in olfactory bulbs is a step toward probing the relationship between these neurons and olfaction.

Calvo-Ochoa and student researchers are also exploring reactions to low-oxygen environments. They place some zebrafish in low-oxygen water. After 15 minutes, the fish are doing remarkably well in many respects, but their sense of smell is impaired. Back in a comfortably oxygenated tank, the fish are now oblivious to scents that signal threats, and they fail to perform their usual freeze-and-drift-inconspicuously-downward maneuver to avoid the perceived threat. Over this coming summer, the researchers will test whether the zebrafishes’ sense of smell comes back. The experiment has implications both for wild fish, whose habitat is changing as increasing temperatures leave less oxygen in the water, and for humans, who compared to zebrafish are more at risk of severe reactions to hypoxia (reduced oxygen), as when struggling to breathe at birth or suffering a stroke.

As one example of the researchers’ work: The team’s study of how zebrafish respond to low-oxygen environments has implications both for wild fish, whose habitat is changing as increasing temperatures leave less oxygen in the water, and for humans, who compared to zebrafish are more at risk of severe reactions to hypoxia (reduced oxygen), as when struggling to breathe at birth or suffering a stroke.

“To me, zebrafish give the best of both worlds, because they’re similar to us,” Calvo-Ochoa says, noting that the species shares over 70% of its genes with humans. “They’re also different in the ways that mean we can learn so much from them.”

Earlier this year Hope College named Calvo-Ochoa a Towsley Research Fellow, a four-year appointment whose recipients receive summer research funding and a sabbatical to pursue scholarly research that benefits Hope students as well as furthering the faculty member’s professional goals. Calvo-Ochoa’s work is also supported by grants from the Kenneth Campbell Foundation ($80,000 over six years), the Michigan Space Grant Consortium ($30,000 in April for student research stipends), the International Brain Research Organization ($30,000) and the National Science Foundation ($460,000). The latter grant supports both ongoing research in the lab (2023-26) and another passion of Calvo-Ochoa’s: increasing diversity in science by funding full scholarships for K-12 bilingual summer science camps held at Hope.

“My first language is Spanish. I identify as a Latinx scientist,” Calvo-Ochoa says. These camps for K-12 students tell the story that “scientists can speak other languages and that Spanish can be used to do science and that there are Mexican scientists.”

Working with zebrafish brains takes consummate skill; they’re incredibly fragile structures. “It gave me a lot of patience to learn how to deal with them,” Calvo-Ochoa says. “You become really good at handling very delicate things. I think my students get nervous when they join the lab and I tell them, ‘You’re going to be in charge of your own experiments.’ And they’re like, ‘That’s never going to happen.’ When it does happen, they feel so proud and accomplished. I think it’s one of the things that they like the most about the lab: that sense of ownership of things, even if they seem very daunting.”

Calvo-Ochoa’s students leave the lab well prepared for research-intensive graduate programs, some with research awards already under their belts. Nathaniel Vorhees ’23 has begun a Ph.D. program at the University of North Carolina, where he is continuing his research on zebrafish neuroinflammation.

“I felt very blessed that I could get such a good research experience. With bigger schools, a lot of times it’s very hard to get into a lab, and then — if you do — you’re just the dishwasher. You rarely get to actively do the experiments. So that’s something I love about Hope: the opportunity to do that.”

“Having done undergrad research,” he says, “I felt well prepared to make that jump.” During his three years in the Calvo-Ochoa lab, he received the Zuidema Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Research and a national travel fellowship to attend a Society for Neuroscience meeting in San Diego.

Skylar DeWitt ’24 has also spent most of her Hope years as a member of the Calvo-Ochoa lab. She received two summer research fellowships from the Michigan Space Grant Consortium, and as a junior she won a prestigious Barry M. Goldwater Scholarship. She has accepted admission to a Ph.D. program in neuroscience at the University of Rochester. “I felt very blessed that I could get such a good research experience,” she says. “With bigger schools, a lot of times it’s very hard to get into a lab, and then — if you do — you’re just the dishwasher. You rarely get to actively do the experiments. So that’s something I love about Hope: the opportunity to do that.”