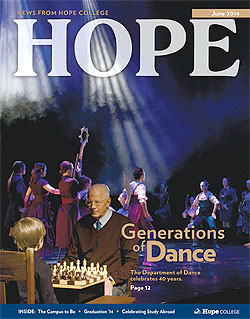

Bringing Fresh Vision to a Classic

Matthew Farmer, MFA | Dorothy Wiley DeLong Associate Professor of Dance

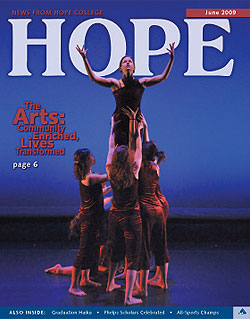

Before the swirling coats were contemplated, before he resolved how 18 roiling bodies would storm across a stage without colliding, before his reimagined storyline took shape, Professor Matthew Farmer spent a year filling his head with Igor Stravinsky.

In his car, on his phone in the breaks between classes and appointments and choreographing other pieces, starting in fall 2018 Farmer looped a recording of “The Firebird Suite.” Over many months he jotted down ideas in notebooks. (“Choreographers should be looking for inspiration every day,” he says.) He marked up a score of the suite with stick figures and “hieroglyphics” to link movement ideas to measures of music. He recalled observed movements and connected them with themes and characters. And danced alone, to put flesh to the ideas.

A funny thing about choreography: It’s about physical movement, but for Farmer it always starts with the music.

“I want to know the silences — the notes between the notes — the music within the music,” he says.

The modern piece by Farmer that 18 Hope College dancers premiered in October 2020 is Farmer’s first foray into choreographing a piece set to Stravinsky’s challenging music. (It took him most of a Christmas break just to analyze the time signatures.) His dance tells a story — though a different one than the 1910 ballet “The Firebird” for which Stravinsky wrote the score.

The ballet is nearly an hour long, but Stravinsky later selected excerpts from it to create the instrumental “Firebird Suite.” That shorter piece serves as the score of Farmer’s “Firebird,” which dancers performed to the Tokyo Kosei Wind Orchestra recording of a woodwind adaptation.

In a departure from the 1910 ballet’s fairy-tale elements, Farmer’s dance portrays a closed community led by a controlling chieftain, and what happens when the chieftain’s daughter finds herself drawn to a visitor who makes her way into the community. The fluttering magical bird of the original is gone; in Farmer’s piece, it’s the chieftain and members of the community who are costumed as birds, and antlers mark the visitor as a deer.

While it’s common knowledge that ballet is composed of formal steps and motion, choreographers know that many casual viewers assume that modern dance is built from scratch. On the contrary; Farmer speaks of the craft of choreography, the five basic elements (time, space, shape, energy and form), and choreographic tools.

“How you manipulate those will create motifs,” he says. “The artistry comes from the creation of the movement; the craft comes in how I’m going to produce it on a bigger scale.”

Dancers may move in unison, or movement may be chaotic, as it is in a climactic section of his “Firebird”: intricately planned, but with no pattern discernable by the audience.

At the choreographer’s behest, dancers accelerate or decelerate; they dance at defined levels from the floor; in retrograde, they reverse movements they’ve just danced, and in canons or rounds, repeat movements briefly or at length.

In the same way that musical counterpoint sets one melody against another, dance counterpoint combines different physical flows. In one striking example in “Firebird,” a fluid, shy pas de deux is interrupted by a mob of dancers in menacing, beaked masks who form circles around the daughter and the deer and keep them apart, the mob’s bare legs flashing fiercely while the duo press gracefully but futilely toward each other.

Although Farmer’s choreography is typically postmodern and abstract, for “Firebird” he created a movement motif for each character. The percussive dancing of the “community” is a drumbeat accompaniment to the sometimes screeching woodwinds. The community’s chieftain is distinguished by large gestures and footfalls. Farmer describes the daughter’s and deer’s motifs as “fluid and round — soft, ethereal.”

In the early stages of a choreography project, he draws on his mental catalog of observed movement. “I’m always looking at people. I’m always analyzing how they move,” he says. As he develops an idea, he reviews remembered motion. “All of the movement I create comes from the real experience that a human has,” he says. “I may expand it into something more ‘dancey,’ but it always starts from an actual human that I experienced at some point. What was the shape, what was the movement—what was the weight of the body when that experience was happening?”

The 18 women who danced “Firebird” are Hope sophomores, juniors and seniors. Many began rehearsing in January 2020 for a performance planned for that April with the Hope College Wind Ensemble. But it was a casualty of the COVID-19 pandemic: Hope students left campus in March to finish the semester remotely. Consequently, Farmer wrapped “Firebird” into the fall performance of H2 Dance Company, a Hope ensemble he directs with Assistant Professor Jasmine Mejia. To replace dancers who graduated in May, nine others joined the “Firebird” cast and learned the material at home during the summer from videos Farmer sent them.

As the fall 2020 semester approached, the dancers returned early to campus for a week of 14-hour rehearsals in a Dow Center dance studio. “Cleaning” the choreography, Farmer demonstrated changes to them. “You have ideas, but they could all come crashing down when you put it on bodies,” he says.

Rehearsals continued several evenings a week once classes began. In October, they shifted to Hope’s Knickerbocker Theatre. Some expansive gestures that worked in the studio did not on that somewhat smaller stage, so updates continued — Farmer modeling, for instance, a new way to swirl an overcoat above one’s head, and movement to reveal the contrast between leotards and legs.

The pandemic had sweeping impact on this production and on dance at Hope more broadly. The dance faculty strategized about how to keep students safe. This year, there’s no physical contact between them in classes or performances. “That forced me to dig deeper as a choreographer into creative ways to express what I’m trying to get across,” Farmer says. He had to consider the distance between dancers and how much time two individuals would spend within a six-foot radius. He completely reworked his choreography of the duet between the deer and daughter, which originally featured partnering and touching — even kissing. Instead, they dance closely, but not face to face.

Another COVID-driven change: no audience could be present for H2’s performance. So in mid-2020, the creative and production teams pivoted to cinematography. Farmer and Mejia decided to go big.

Putting their heads together with lighting designer Eric Van Tassel, sound designer Eric Alberg and the Hope Video Services team, they brought in a boom and a Steadicam® — video equipment on a gyroscope that allowed the operator to keep shots steady while moving among the dancers, which lets viewers see things they wouldn’t from a theater seat. “Some moves and moments that look great in ‘real time’ fell completely flat on camera,” says Farmer, who watched through a monitor during filming. “I had to change choreography on the fly, teach it to the dancers, and then do another take of that dance scene or section.”

Ordinarily, ticket sales offset production costs, but COVID took tickets off the table. Funds available to Farmer through his endowed professorship paid for the “Firebird” costumes, and support by Patrons for the Arts covered some filming costs, plus the copyright fees triggered by the decision to stream the show.

Filming took 54 hours over eight days. The dance company performed the entire program three times in the empty Knickerbocker so filming could take place from a range of angles. Real-time editing happened throughout, and then the technical team spent three days selecting from more than 20 hours of footage to create the H2 repertory concert dance film “In This Time.” It premiered online on October 16 and streamed again the following night, with a different “Firebird” dancer in the role of the daughter each evening.

“There’s nothing like seeing dance live. You can’t replicate seeing real humans in front of you,” Farmer says. But forging ahead during the pandemic has persuaded him and his colleagues that there’s give and take, he adds. Many people never venture into a live dance performance. When it’s accessible online, “maybe seeing it only once or twice inspires them to come and see it live.”

“Firebird”

Choreography by Matthew Farmer

Premiered October 16, 2020

H2 Creative Directors

Matthew Farmer, MFA, Dorothy Wiley DeLong Associate Professor of Dance

Jasmine Mejia, MFA, Assistant Professor of Dance Instruction

Hope College Designers and Technical Staff

Costume Designer: Darlene Veenstra, Costume Shop Director

Lighting Designer: Eric Van Tassel, Assistant Professor of Lighting and Sound Design

Sound Technician: Eric Alberg, Technical Director for the Performing Arts

Film Editor: Jose Velasquez, Video Services

Cast

Chieftain: Caitlyn Enright ’21

Chieftain’s daughter: Eleanor Deakin ’21 and Celine Carroll ’21 (sharing the role at alternating performances)

Deer: Katherine Tracy ’22

Community members: Emma Barnhart ’21, Olivia Coolman ’21, Mylee Graham ’22, Sara Harris ’22, Emily King ’21, Hannah O’Neil ’22, Liv Panozzo ’21, Sophie Rossmiller ’21, Tia Santi ’21, Karsyn Schrag ’22, Haley Soderbloom ’21, Greta Sorensen ’22, Caitlyn Walsh ’21, Ashley Zardus ’21 (and Ellie Deakin and Celine Carroll, when not dancing in a featured role)