Jeremiah and Lamentations Through 16th-Century Eyes

Jeff Tyler, Ph.D. | Professor of Religion

Hope College church historian Dr. Jeff Tyler has spent the past 10 years in conversation with Reformation writers. As the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation approached, he combed through books, lectures, sermons and other texts by nearly 50 Reformation thinkers to assemble an anthology of Protestant Reformers’ comments on the Old Testament books of Jeremiah and Lamentations.

Swiss theologian Johannes Oecolampadius, born 1482. British poet and cleric John Donne, born 1572. Spanish priest St. John of the Cross. John Calvin. Martin Luther. Dozens of others.

In April, Tyler’s book will be released as volume 11 of InterVarsity Press’s Reformation Commentary on Scripture series (which is to total 29 volumes when it’s completed in 2026). Designed as a resource for preachers, teachers and scholars, the series is assembling an unprecedented range of Reformation-era texts commenting on every passage in the Bible.

Writers in that day were extraordinarily prolific; Tyler calls the period “one of the golden ages of biblical interpretation.” Buoyed by the invention of the printing press, he explains, preachers and theologians doubled down on rigorous biblical analysis — and in the absence of copyright law, editions of their work abounded, leaving today’s church historians with a treasure trove.

“People were optimistic that the right books and texts could solve the problems of church and society. Enormous energy was devoted to commenting on the biblical text,” Tyler reports. “The rapid spread of expertise in biblical languages — Greek and Hebrew — combined with a community of scholars across Europe who all spoke Latin. They could read each other’s interpretations and generate an international discussion about the Bible.”

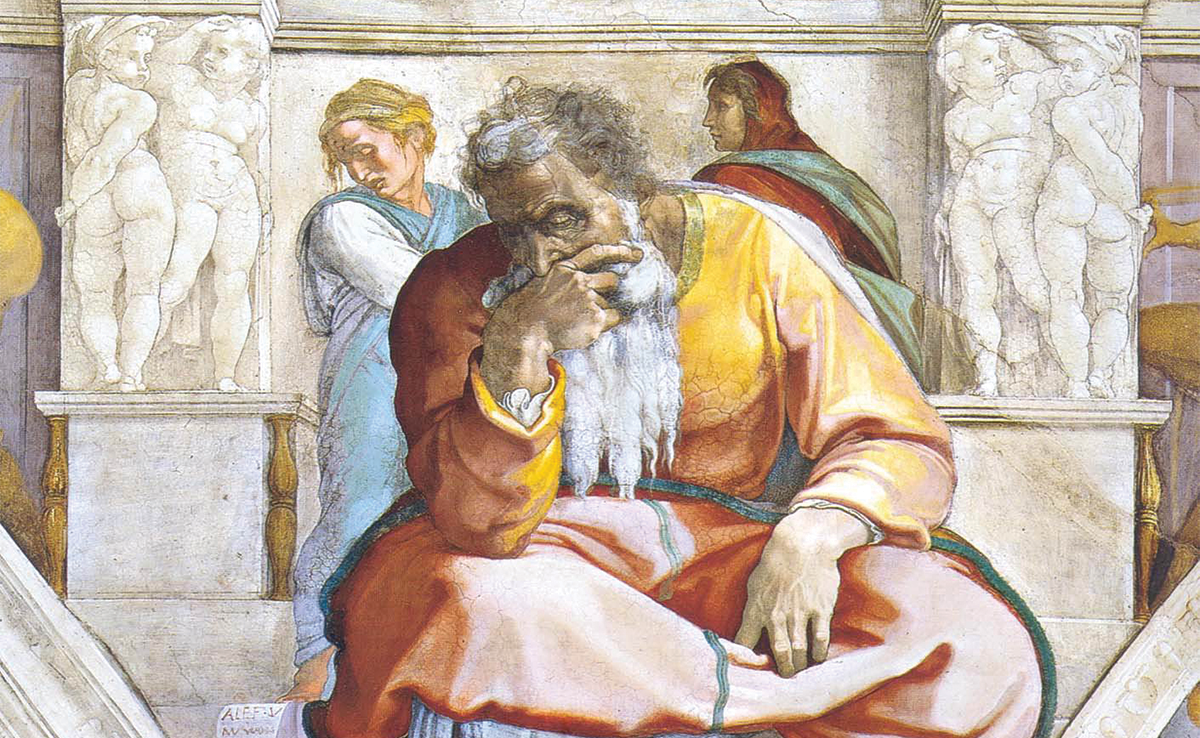

Jeremiah and Lamentations don’t get much press today. Not so during the Reformation. Jeremiah weaves together prophecy, reflections on his own life, and a theme profoundly relevant to Reformation thinkers: the dissolution of a reformation in ancient Judea, specifically the reforms of King Josiah that his sons overturned. “That’s what some of these commentators were worried about in Europe in the 1500s: that their reformation was failing as well,” Tyler says.

“There are places where Jeremiah reflects on the difficulties of faith and the painful tasks that God may give a person. There are two places where, like Job, he laments that he had been born; he cries out to God regarding his miserable life, the painful tasks he must undertake, and the hatred he receives from nearly everyone. This human, deeply vulnerable Jeremiah intrigued me.”

Suffering and faith are themes in Lamentations, too. It is a poem of mourning. “There, commentators reflect deeply on human emotions, and also on thinking about the suffering in Jeremiah’s day when Jerusalem was destroyed. There are descriptions of devastation, death and cannibalism in Lamentations, along with these gorgeous sections about trust in God’s faithfulness — that God will not forsake us, in the end.”

Some of Tyler’s students chafe at reading books about the Bible; they tell him they just want to read the Bible alone. He responds this way: “We read the Bible from our own context and we have insights because of that context. But we’re also limited in what we see. This is the importance of reading these people from other periods. They open up the Bible to us. The history of Christianity teaches us the Bible in a way that just reading the Bible itself doesn’t do.”

Through the lens of modern psychology, 21st-century readers recognize and sympathize with Jeremiah’s struggle, Tyler suggests. Sixteenth-century commentaries offer alternate perspectives. Some Protestant Reformers wrote of Jeremiah’s steadfast faith, but others saw him as a failure when he lost his nerve — and they declared he was a poor example for Christians to follow. Yet another stance was common among Catholic commentators such as St. John of the Cross, who singled out the prophet Jeremiah’s struggle as evidence of his close proximity to God — to which St. John related, as a mystic.

There was no road map for Tyler to follow as he explored these writings about Jeremiah and Lamentations. Some are well-known and easy to find, such as the five volumes (in English translation) of Calvin’s commentary on the books. Others took detective work. Luther never wrote or lectured about Jeremiah; Tyler found his comments on the book embedded in cross-references within Luther’s lectures on Isaiah and the minor prophets.

Many of the texts Tyler pored over were in Latin or in German. Over the past decade he created the first English translation of many of them; he also updated some prior translations of Calvin’s work. His book reproduces 15th- and 16th-century English translations of French and Italian Reformers’ writing that Tyler considers reliable, but he updated archaic English that would baffle today’s readers. Works by Reformers who wrote in English, such as Donne and John Knox, will appear in the book as they did in the 1500s and 1600s.

Tyler completed the project with even more appreciation for the care and expertise Reformers brought to biblical analysis as they worked through every verse and chapter in detail, applying encyclopedic knowledge of the Bible and biblical geography.

There are places where Jeremiah reflects on the difficulties of faith and the painful tasks that God may give a person… This human, deeply vulnerable Jeremiah intrigued me.

Reading lesser-known Reformers’ work, he found several especially engaging. Luther’s pastor and colleague Johannes Bugenhagen “writes profoundly for the everyday Christian and for the church,” Tyler says. As a historian, he enjoyed Bavarian musician-theologian Nikolaus Selnecker’s comments on the behavior of everyday people of his time — and the misbehavior of their rulers. “He is terrified that the Muslim Turks will be God’s new source of punishment on wayward Christians. Selnecker’s anxiety about invasion echoes our fears about victims of war and refugees today.”