A Gift with Gratitude for an Unforgettable Act

Search for Dr. Latif Jiji’s name online, and you’ll find articles in publications like The New Yorker and the Washington Post about his unique role as owner, with his wife Vera, of Manhattan’s only vineyard — in the couple’s 15-foot by 45-foot backyard.

You’ll find information about the respected texts that he wrote during his career as a professor specialized in mechanical engineering at The City College of New York.

You’ll find accounts celebrating some of the many awards he received as an acclaimed teacher and mentor during some 50 years in higher education.

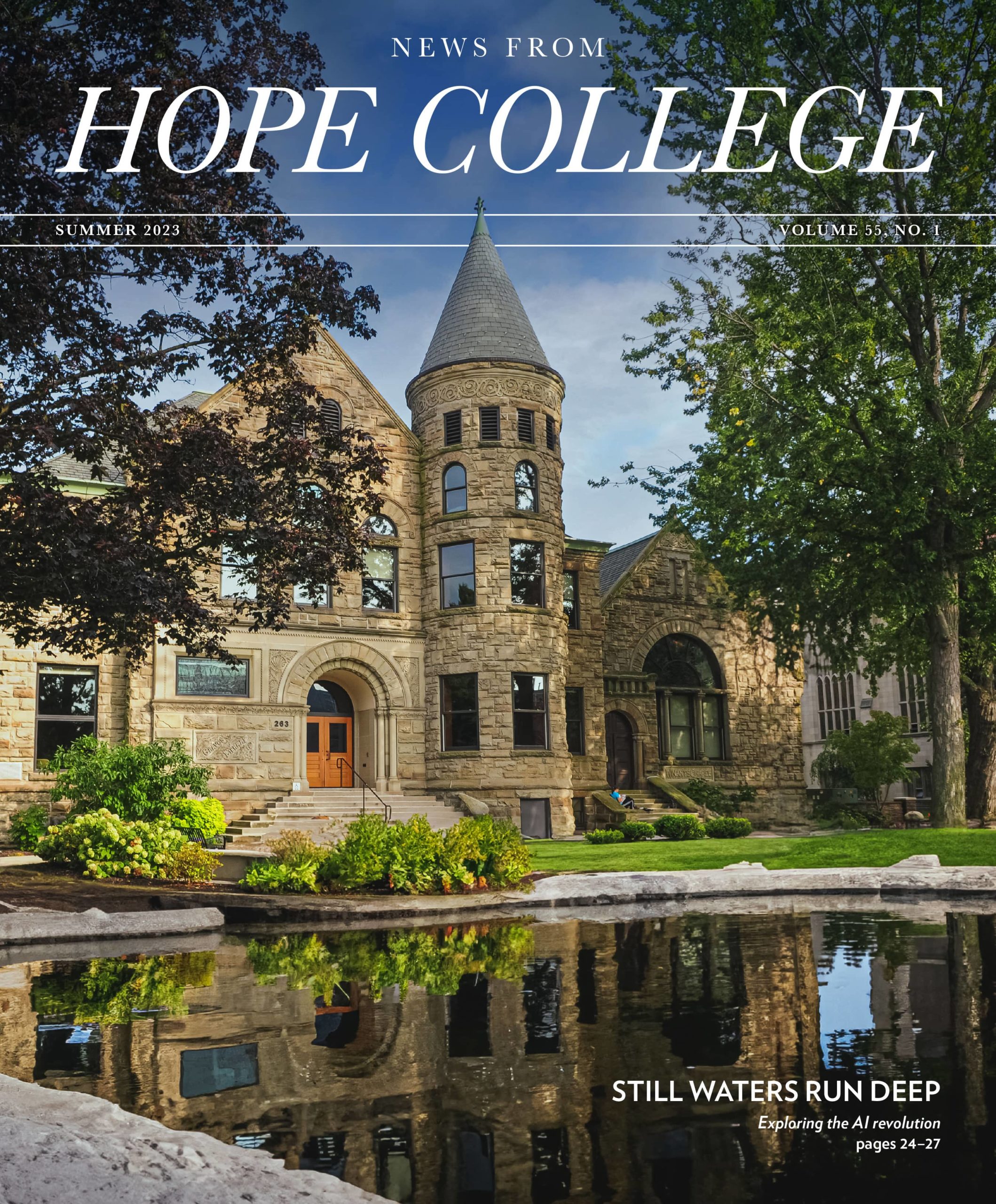

But there’s another story that precedes those: of how he happened to land at Hope College from Basra, Iraq, in 1947. It’s the reason that he returned on Monday, Dec. 11, 2017, 70 years to the day after he first arrived: to say thank you.

As a Jew in the Iraq of the 1940s, Latif faced limited prospects. Jews, Christians and Muslims had previously coexisted peacefully in his hometown, but political developments across recent years had put that era in the past. Jews became targeted for violence — there were murders elsewhere in Iraq — and opportunities melted away. “I was qualified, but I knew that I was not going to be accepted to one of the universities in Iraq,” he said.

Hope’s parent denomination, the Reformed Church in America, still had a significant mission presence in Iraq at that time, including the School of High Hope (established by 1899 Hope graduate John Van Ess) in Basra, which two of Latif’s sisters attended. He was instead at the local public school, but one of his teachers had attended Hope and encouraged him to apply. Latif gained admission for the fall 1947 semester, but at that point things went wrong.

“It was late in the fall of 1947 when I finally obtained all necessary documents to allow me to leave Baghdad for the USA,” he recalled. “My last stop was at the American consulate in Basra to obtain a visa. To my horror, I was refused a visa because my admission to Hope College was for September, which had already passed. Only admission to the spring term of 1948 would be acceptable.”

“This news shattered me,” he said. “The various Iraqi travel permits I had struggled to obtain were only valid for short periods. To have all permits, including a visa, valid simultaneously was extremely difficult.”

“Adding to the pressure of this tight time constraint was a major political development: The United Nations had just approved the partition of Palestine [Nov. 29, 1947], creating a hostile environment for Jews in Arab countries,” Latif said. “Getting admission for the spring 1948 term quickly before other travel permits expired was urgent.”

He anxiously sent a telegram to the college, seeking spring admission. Fortunately, Hope’s director of admissions, Albert Timmer ’23, responded almost immediately, and Latif was soon on his way. “Had the admissions telegram arrived just a few days later, other permits would have expired and my travel to the U.S. would have been derailed,” Latif said.

Timmer’s thoughtfulness continued after Latif’s arrival. Considerate of Latif’s faith tradition, he arranged an introduction to the only Jewish family in town at the time, Louis and Helen Padnos and their sons Stuart ’42 and Seymour ’43, who extended Latif’s first dinner invitation in Holland.

Hope at the time didn’t have an engineering major, so Latif spent only three semesters at Hope, transferring to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for his Bachelor of Science. He notes, though, that he was well served by his preparation at Hope.

“I consider Hope to be the foundation of my career,” he said. “The outstanding education I received at Hope was instrumental in being admitted to MIT to complete my undergraduate education.”

He also feels that Holland and Hope were the ideal introduction to America.

“I had no trouble adjusting. I had no trouble assimilating,” he said. “It would have been overwhelming for me to start at MIT. I was extremely fortunate to start in a small, friendly town at a small, friendly college.”

Holland was uncannily tranquil, as he found while boarding off campus. “When I asked the landlady for a key to the home, she said, ‘I don’t have a key. We don’t lock the door,’” he said.

Morning Chapel at Hope was mandatory at the time (and through the latter 1960s) and, although he was Jewish, Latif was required to attend.

“People ask me, ‘Did you mind?’ No, I didn’t mind,” he said. “I was in America, learning something new. It was fine with me.”

After graduating from MIT in 1952, he completed an M.S. in mechanical engineering at Carnegie Institute of Technology in 1953, and an M.S. in aeroscience and a Ph.D. in mechanical engineering at the University of Michigan in 1958 and 1962 respectively. At U of M he was mentored by an engineering faculty member who still had Hope in his future: Dr. Gordon Van Wylen, who was Hope’s president from 1972 to 1987.

Latif’s visit in December also provided him with a chance to meet with Van Wylen, who still lives in Holland. Van Wylen had attended MIT as a graduate student, and the two reminisced about a professor who heavily influenced the way they each taught. Latif also shared how Van Wylen had likewise influenced him. “You used to invite the graduate students to your home,” he told him. “I learned that from you, and so when I became a professor I used to invite students to my home because I remembered how important that was to me.”

Latif spent 60 years teaching in higher education, first at the University of Toledo and New York University and then, from 1954 until retiring in 2014, at The City College of New York. He received multiple teaching and mentoring awards at The City College, including the 1988 Outstanding Teacher of the Year Award. He received significant external recognition including a Fulbright Scholar award, the 2008 Ralph Coats Roe Award from the American Society of Engineering Education for outstanding teaching and contribution to engineering education, and the 1997 Faculty Advisor Award presented by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

The vineyard and winery that he and his wife run happened by accident. Latif planted a small grapevine in the backyard in 1977, and as the years passed it all but took over, today climbing the entire height of the family’s four-story Manhattan townhouse and across a rooftop trellis. In 1984, the vines produced 24 pounds of grapes, a number that has also grown. The record is 712 pounds, with 400 to 700 pounds being typical.

Wine-making has a family history: Latif’s father had made wine as a hobby in Iraq. Latif and Vera named their label Chateau Latif, inspired by the renowned Chateau Lafite label. Harvesting and production provide an opportunity for family and friends to come together, resulting in 80 to 150 bottles of white wine per year.

As one reflection of his appreciation for the college, he presented one of those bottles to Hope during his visit. Its hand-drawn label shows the townhouse on one side and Graves Hall and the Hope College Arch on the other.

Later, though, he offered a second gift, establishing a scholarship in the name of Albert Timmer ’23 and Timmer’s secretary Dena Walters for making a difference, not only to him but to his 62 descendants and other relatives now in the U.S.

“I consider receiving the timely admission to Hope College the single act that changed my life,” Latif said. “I am grateful to Mr. Timmer and to his secretary, Mrs. Walters. I include her because I now know that the efficiency of an office rests on the shoulders of people who normally are not recognized and often blamed when things go wrong.”

“It is my sincere hope that the beneficiaries will remember these two individuals who helped a young man from Iraq to realize his dreams – and will be inspired to do their part to assist others who are in need,” he said.