Sport and Religion

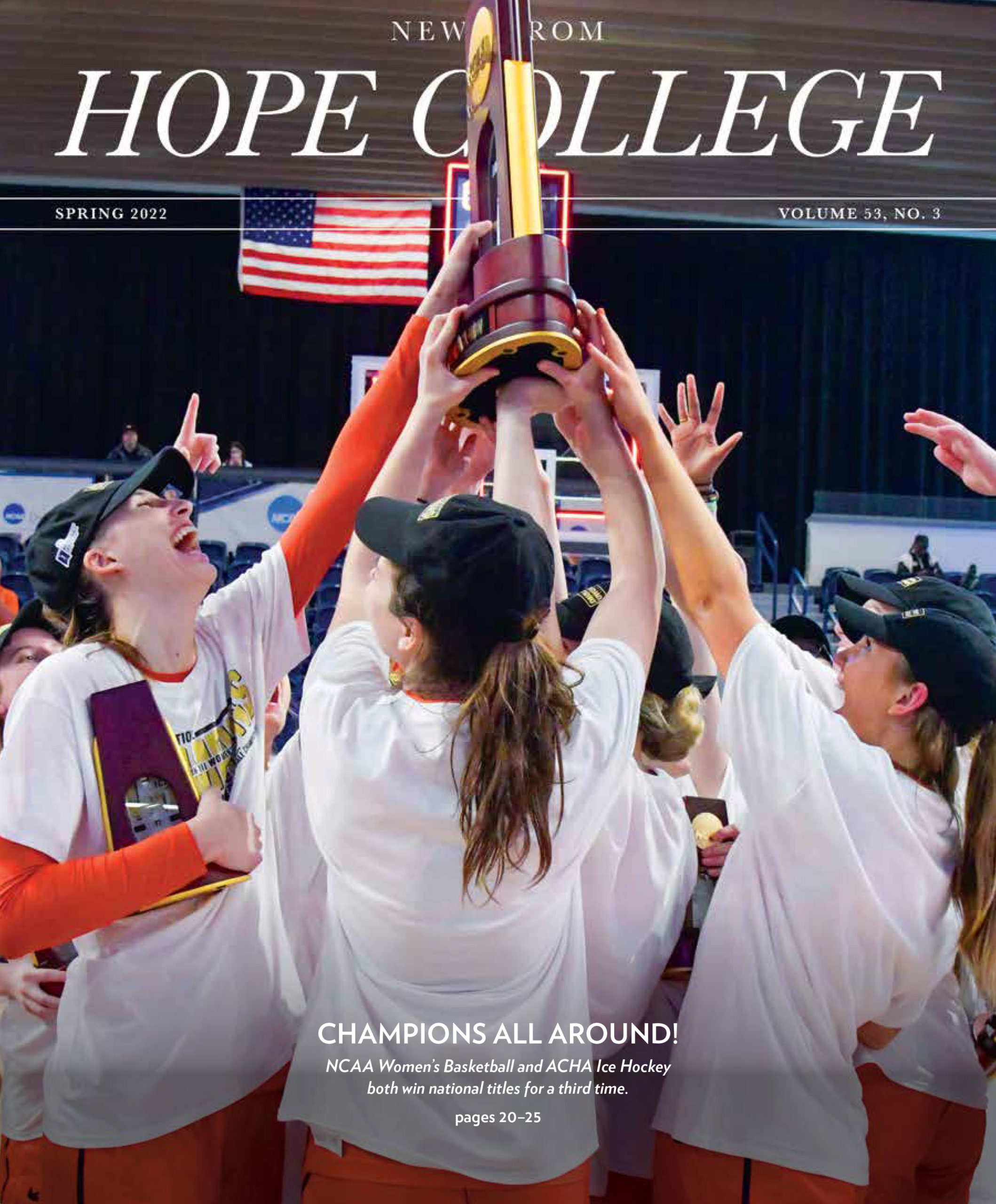

In America — with its foundational tenet of religious freedom and expression and with its fanatical devotion to sport participation and consumption — a prominent and perplexing marriage weds fierce competition and sincere faith on our playing fields, televisions, and newsfeeds. In kneeling Tim Tebow and post-game-midfield prayers, in evangelistic Athletes in Action and in a no-Sunday play policy for Hope College’s 22 intercollegiate teams, the social institutions of sport and religion seem to walk hand-in-hand down the aisle of American life on a regular basis, joined together at the hip and in seeming lock step to help their followers build character and faith.

Yet, upon further review, examples abound when these two devoted partners can appear to be strange bedfellows at best. Turn on ESPN’s SportsCenter almost any day of the week to find the country’s newest sporting controversy simply not jiving with ethical behavior, let alone Christian principles. Sport-and-religion compatibility is questioned when competitive priorities overpower moral sensibilities.

So, why do we even combine the practices of sport and religion in the first place? (And when we talk about sport and religion, let’s be honest, we are usually exclusively thinking about sport and Christianity.) Why are Christian athletes more vocal about this combination than those from other major religions? And what does this all look like and are there lessons to learn at Hope College, a vibrantly Christian school with an excellent athletic program?

At first blush, it makes sense that sport and religion would be attracted to each other. When juxtaposed, they seem to be more the same than they are different, their relationship so seamless and symbiotic that even eHarmony would deem them to be good mates.

And what does this all look like and are there lessons to learn at Hope College, a vibrantly Christian school with an excellent athletic program?

To wit, renowned American sport sociologist Jay Coakley surmises in his seminal text, Sports in Society: Sport and religion both have places for communal gatherings and special events; both have procedures and dramas linked to personal betterment; both emerge out of the same quest for the perfection of the body, mind, and spirit; both have heroes and legends; both can evoke intense excitement and emotional commitment; and, both can give deep personal meaning.

“Historically, sport and religion have been good for each other in ways that we can quantify,” adds Dr. Chad Carlson ’03, associate professor of kinesiology. “Christianity has used sport for its purposes — increasing followers, increasing visibility through the mainstream media — and sport has used Christianity for enhancing the meaning behind participation, as a way of creating solidarity and unity on teams, as a way of providing comfort and peace amongst all of the uncertainty of sport. So they’ve used each other and that’s why their relationship seems so close and obvious.”

Skeptics, though, like to trot out the obvious disconnect between sport and religion when humility succumbs to pride, when an opponent is viewed as a hated enemy rather than an equally loved child of God, when competition casts dark shade over compassion, and when the “me-before-you” refrain strikes a selfish discord. Even Jesus said, “the first shall be last and the last shall be first.” There may be no greater dissonance for a Christian competitor than that.

Or, maybe not.

“I don’t want to get rid of this whole project of Christians playing sport just because we sin or just because our emotions get the best of us from time to time. That happens in every area of our lives,” reasons Carlson, whose research on sport and religion with colleagues at rival Calvin College can be viewed as the epitome of cooperation between sport and religion.

“By focusing on God, we want to play with principles that are compatible with our faith. Yes, we want to win at Hope, but we are going to strive to do so in a manner that would make God happy. And really, that has nothing to do with winning. That has to do with focusing on our own hearts and how we are growing in the process.”

Admittedly, scoring that kind of affirming, faith-based goal in educational athletics is not a one-off. It takes daily lessons to teach and encourage college student-athletes to play their sport in a manner that is representative of Hope’s — and their own — Christian mission. No doubt, the many Bible studies and corporate prayers that are Hope team norms touch hearts and minds to play like and for Jesus. But intentional life coaching reinforces values reflective of “doing it the right way, carrying ourselves on the field the right way,” says Dr. Leigh Sears, head coach of the women’s soccer team. “The women on my teams know that as Christians, they can play really, really hard and still be super respectful of their opponents as well.”

To that end, Sears and her captains have planted and grown a team culture that revolves around an ethos of both self-improvement and servanthood, backed up by biblical scripture. Together, coach and student-athletes have thoughtfully implemented several team themes over the years — Team Over Self, Actions Over Emotions, Positive Attitude, Work Hard, and Team of Grace — making their message as applicable to three months’ worth of practices and games as everyday life, even beyond the college years. Win or lose, Sears — a kinesiology faculty member whose teaching specialty is human nutrition —makes sure her players view victory and defeat on the field and off in the healthiest way possible.

“Whether we win or we lose, we should still be the same people,” says Sears whose teams do more of the former than the latter, having a 48-11-7 record and two NCAA tournament appearance in the last three years. “When we shake hands (after winning a game), we really want to shake hands, and we want to look our opponents in the eye and say ‘good game’ like we mean it.”

And if they lose?

“Same rules apply. We congratulate our opponent, and life goes on. Our puppy did not just get killed in a parking lot,” she says in her typically colorful way. “By the grace of God, we’ll all get to wake up and play tomorrow.”

Her point: Sport may be vulnerable to 50-50 outcomes, much like anything else in life, but student-athletes’ reactions to those outcomes — be they agreements or differences, successes or frustrations — should embody a doctrine of merciful consistency.

And so it goes for each of Hope’s 15 other head coaches, too. Competition and faith in perspective. As much as all of Hope’s intercollegiate teams want to win an MIAA championship and advance to NCAA post-season, they realize the real reward is engaging Christian fundamentals and fair-play essentials far beyond the realms of church and win-loss columns. Whether blatantly expressed or softly evident, the teachings of sport and religion insist that their adherents use character-building and faith-filled lessons for the sake of Christ and community, in careers and calling.

The collective sport-and-religion debate—contentious at times, gracious at others—winsomely teaches any Hope student-athlete who bravely wades into the fray that the lessons divined from putting faith and play in action are applicable to all of life, not just four athletic collegiate years.

“Not many experiences demand the personal introspection, the practiced expression of beliefs and a view of the nature of humanity as the physical, psychological, and emotional strivings toward a common goal (found in both sports and religion),” says Melinda Larson, co-director of athletics and associate professor of kinesiology. “All of these experiences will impact our student-athletes for entire lifetimes.”

We conjecture first, of course, that coaches and administrators are the ones doing most of the teaching on this, that they are the purveyors of profound tutorials to their younger charges at the intersection of faith and competition. “But it is my personal belief that student-athletes’ faith can have some of the greatest impact on the lives of their coaches as well,” adds Co-Director of Athletics Tim Schoonveld ’96, also the director of academics for Hope’s Center for Leadership and an assistant professor of kinesiology. “I know they’ve had an great impact on me.”

Schoonveld sees it in Isaiah-eque stylings: the lion of sport shall lies down with the lamb of religion, and a small child will lead them. Though no longer small (she stands 5’9”) or a child (at 22 years of age), senior soccer and basketball player Elizabeth Perkins is one such Hope student-athlete whose impact extends to those much older, from coaches to athletic directors to even fans in the stands. Her energetic, hard-nosed competitor identity, obvious and respectful, is only surpassed by her committed Christian appellation, also clear and reverent. Admittedly, getting those two priorities to coexist peacefully in one heart was no overnight epiphany but a slow roll toward revelation.

“I identify strongly as an athlete. I became a soccer player before I became anything else,” admits Perkins, a Spanish and psychology double major who plans to attend Truett Theological Seminary in Waco, Texas, after her Hope graduation so she can later pursue a career in sport ministry. “But then as I grew and matured and came to know Jesus, the more I realized where my true identity is supposed to be. There is this large book with 66 other books that is telling me who I am and what that means. That’s when (my identity) flipped, it became cross-cultural, and I placed my identity in something that is far less wavering than sport. Now, Jesus takes up most of my heart space but sports are a close second.”

When asked whether the level of accepted behavior for Christians in sport is judged on a higher plane than non-Christians, Perkins, a native of Eaton Rapids, Michigan, is quick to reply with sagacious maturity: “Of course. I believe Christian athletes should be held to a different standard and that standard is Christ. But He is for all Christians, right?”

It’s a rhetorical question. She already knows that answer, and it will govern her spirit and future in sport and religion in the years ahead. And it will too for Nick Holt. A sophomore baseball player from Muskegon, Michigan, Holt has the same hopes to influence others’ faith and play but as a high school teacher and coach. The lefty pitcher and sometimes centerfielder is athletically and religiously devout, and he spreads the gospel of Abner Doubleday as lovingly as the Gospels of Jesus Christ. Already engaged in youth ministry at a Holland-area church, the warm and engaging Holt believes that being a true follower of both sport and religion is “about having deeper relationships and not just with Christians but those who are not. Being on a team where everyone is at the different place in their faith walk is like the ‘real world,’” says the integrated science education major. “And that is great; I need that. Because otherwise, what’s the point? Jesus didn’t tell me to go live with my beliefs and abilities away from others. I need to be in this world, wholly in this world, and that includes sports.”

“The really, really important point is that sport is a gift from God but since it’s in this world, it is not excluded from our brokenness and our sin,” Perkins adds. “So sport needs to be redeemed, that is the key, so that it does not have to be separated from faith.”

The collective sport-and-religion debate — contentious at times, gracious at others — winsomely teaches any Hope student-athlete who bravely wades into the fray that the lessons divined from putting faith and play in action are applicable to all of life, not just four athletic collegiate years. Despite competitive derision or personal differences, the message combed from the married mesh of competition and faith is one of bilateral inclusivity, not mutual exclusivity, and it looks more like a pretty present than a heavy burden. Because in the end, the story of sport and religion is a redemption story, a tale of rising and falling but getting back up to play and believe again.

Author Eva Dean Folkert ’83 is a regular contributor to News from Hope College, but she has also lived the subject of this story directly. She is a former assistant professor of kinesiology and co-director of athletics at Hope, where she has also taught a Senior Seminar entitled Sport, Society, and the Sacred.

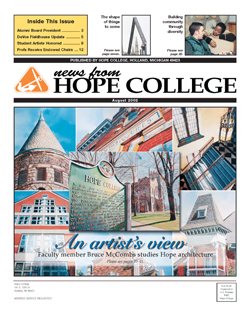

The illustrations accompanying this story are watercolors by Bruce McCombs, professor of art.